Birth of U.S. Marine Corps Base

Birth of U.S. Marine Corps Base

Quantico, Virginia in 1917

It's called the "Crossroads of the Marine Corps," and during its 93 year tenure on the approximately 100 square miles of land located along the western bank of the Potomac River, Marine Corps Base Quantico has been a training site for Marines and a birthing place of Marine Corps concepts.

Prior to Marines arriving here in 1917, the land was owned by the Town of Quantico. At the turn of the century, the Quantico Company was formed on Quantico Creek. The company, which promoted the town as a tourist and excursion center, set up tourist sites, such as refreshment stands, boats, and beaches with dressing rooms to promote business.

The large white building at the top, built in 1919, currently houses the Defense Printing Agency, self help and drivers improvement office. Directly across the railroad tracks are the buildings that comprised the town of Quantico. Quantico still holds its claim to fame as the only town in the country completely surrounded by a military base.

By 1916, the Quantico Company began advertising Quantico as "The New Industrial City," and pushed for industry to come to the area. At the same time, the Quantico Shipyards were established on the land that is now located by the Naval Medical Clinic to build ocean freighters and tankers. With growing tensions of war in Europe, the construction of U.S. Navy ships was a major money-maker for the Quantico Shipyards.

"I remember lots of hammering and noise going on in the back of the town," said John Brown, who was born in 1895.

Brown, a resident of the Brook Point Nursing Center in Stafford, grew up in Fredericksburg in the early 1900's and was a shoe shiner at a Quantico Town barber shop for 38 years, up until the end of WWII.

While the Town of Quantico was rapidly growing as a fishing village, excursion center and a shipbuilding center in early 1917, the town was not large or significant, and was suffering many financial difficulties.

Around the same time, then-Major General Commandant of the Marine Corps, Major General George Barnett, sent a board to find possible sites for a new Marine Corps base in the Washington, D.C., vicinity.

It wasn't to long after that the Crossroads of the Corps was established and the name "Quantico" would become immortalized in military history.

In 1917, Marine Barracks, Quantico, was established on the land currently occupied by today's Base. Marine Barracks personnel consisted of 91 enlisted men and four officers.

Brown recalls a time when the Town of Quantico and its newly established neighbors, the Marines of Marine Barracks, Quantico, were much different than today's Quantico area.

Quantico is the home of Marine Helicopter 1, the first Marine helo squadron. Here Marines load a helo as they test the aircrafts troop movement capabilities.

Brown referred to the training and preparation Marines made here for deployment to Europe during both World Wars while he worked at Quantico.

"There were horses and carriages, and buggies," he said. "I remember soldiers [Marines] training there for something they weren't too certain of."

As technology grew and expanded, so did Quantico. Thousands of Marines were trained here during World War I, and by 1920, the Marine Corps schools were founded, as then-Commandant, Col. Smedley D. Butler put it, "to make this post and the whole Marine Corps a great university."

These schools eventually developed into today's Marine Corps University, where most Marine officers begin their careers and many enlisted types keep up with their primary military education.

Quantico also had several other firsts, to include a first in Marine aviation and warfare doctrination. The first Marine Aircraft Wing was developed here, as well as the Corps' first helicopter squadron - Marine Helicopter Squadron One. HMX-1 was the first helicopter squadron to provide rapid transportation of U.S. Presidents. It continues that mission today.

In 1934, Amphibious Warfare Doctrine, along with special amphibious landing crafts for WWII were developed here.

Brown also remembered one incident he had with several Marines during Morning Colors at the Barracks just a few years after the base was established.

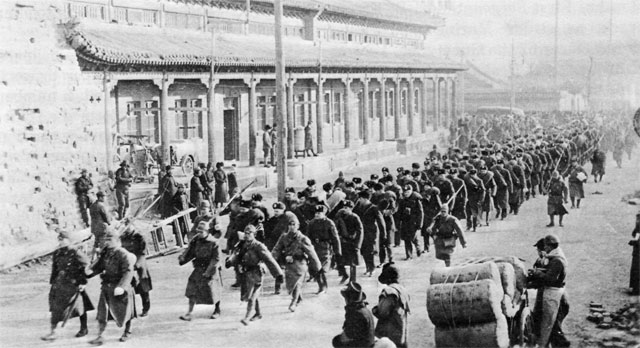

Students of the 1st Officers Training Camp dug trenches as part of their training. Officers were first trained here in August 1917.

"When that flag came up, a Marine told me to put my hand over my heart," he said. "He told me that if I was going to salute, that I had to stand at attention. I haven't forgotten to salute."

Since his birth, Brown has had the opportunity to experience many things in the Quantico area, to include many of the base's developments. Quantico was the birthplace for the first Marine Corps newspaper, the Quantico Sentry; the Advanced Base Force, which was the predecessor of today's Fleet Marine Forces; and a doctrine that gave the guidelines for training the first Naval gunfire specialists.

In 1987, the Marine Corps Development and Education Command here was changed to the Marine Corps Combat Development Command, signifying Quantico's role in the 21st century Marine Corps.

Over the years, Quantico has served as a birthing place for concepts and ideas that have since developed into essential components to the Corps' mission.

From the first 95 men who made up Marine Barracks, Quantico, which Brown remembers as only a handful of Marines training for WWI, to becoming the foundation of today's formal Marine schools and home of HMX-1, Over the course of it's "lifetime," Quantico has truly lived up to it's motto, "Semper Progredi," always forward.

Those Who Came Before Us

What is now known as the Crossroads of the Marine Corps was once seen as five miles of quiet, lush forest that bordered the Potomac River.

According to records, this is how the Algonquin Indian tribe known as Manohoacs saw the land when they inhabited the area just north of Quantico in the 1500s.

As a matter of fact, the name "Quantico" comes from the Native Americans and has been translated to mean "by the large stream."

Other accounts show that the area was first visited by European explorers in the summer of 1608. But, it wasn't until later in the year that major land owners started to appear.

After the turn of the century, the area became popular because of tobacco trade in Aquia Harbor. Because traveling on muddy roads in those days was slow, many villages sprung up along the river and its inlets. Additionally, the area was a bustling stopping point on the North-South routes between New York and Florida.

Early settlements and plantations rooted along the flatlands bordering the Potomac. The hills west of the river remained essentially uninhabited until the early 1700s.

Prince William County was organized in 1731 when the "Quantico Road" was also opened. This road gave vital access from the western part of the county to this area. By 1759 the road stretched across the Blue Ridge Mountains into the Shenandoah Valley.

The first military presence at Quantico came during the Revolutionary War, when the Quantico Creek village became a main naval base for the Commonwealth of Virginia's 72-vessel fleet on which many Virginia State Militia served.

The land was first visited by the Marine Corps in 1816 when a group of Marines traveling by ship to Washington had a slight setback. Their vessel was halted by ice in the Potomac forcing them to debark and march to the town of Dumfries. Here they met a young Captain Archibald Henderson who lived close by. A generous-natured man, Henderson hired a wagon for them and sent them on their way.

During the Civil War, control of the Potomac River became very important to both sides of the two armies. The Confederates picked the Quantico Creek area on the Potomac to set up their gun batteries. This enabled them to make full use of several points where their artillery could reach anything on the water, thus deterring Union use of the water highway. One of these sites included "Shipping Point," the present day site of the Naval Medical Clinic here.

While battles took place in Manassas and Fredericksburg, Va., the gun positions around Quantico were used until the end of the war. After a 12-day battle at the Spotsylvania Courthouse where the Union lost about 25,000 soldiers, the war moved out of the Quantico area.

Following the war, railroads became a more integral part of transportation. In 1872, the Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac railroad was formed when several railroads north and south met at Quantico Creek. This railroad still runs through the Base and is used daily.

The village came to be called "Quantico" and was built by the Quantico Company. This was the start of a thriving tourist and fishing town that would later be known worldwide as Marine Corps Base Quantico.

MCRD "Marine Corps Recruit Depot"

MCRD "Marine Corps Recruit Depot"