Sunday, April 29, 2012

United States Marine Corps

First Marine Corps Aviator

22 May 1912

On May 27, a 250-pound bronze bell is scheduled to be showcased in the Memorial Day ceremony at Veterans Memorial Park, Pensacola, Fla. It will be on display in its permanent home in the tower on Aug. 20, at the 100th anniversary celebration of Marine aviation. That will symbolize the sacrifice of Marine pilots and crew members since their branch first took flight 100 years ago.

Lieutenant Colonel Alfred Austell Cunningham (March 8, 1881 - May 27, 1939) was a United States Marine Corps officer who became the first Marine Corps aviator and the first Director of Marine Corps Aviation. His military career included service in the Spanish-American War, World War I, and U.S. operations in the Caribbean during the 1920s.

Early life and career

Cunningham was born in Atlanta, Georgia. His interest in aviation began in 1903 when he watched a balloon ascend one afternoon. The next time the balloon went up he was in it and from then on he was considered himself a "confirmed aeronautical enthusiast". He enlisted in the 3rd Georgia Volunteer Infantry regiment during the Spanish-American War and served a tour of occupation duty in Cuba. He spent the next decade selling real estate in Atlanta. During this time evinced an interest in aeronautics, making a balloon ascent in 1903.

At the age of twenty-seven, he returned to the military life, mostly because he thought that he would be given the opportunity to fly. He was commissioned as a 2nd lieutenant in the United States Marine Corps on January 25, 1909.

Supporter of Marine Corps aviation

As a Lieutenant, Alfred Cunningham retained an interest in aeronautics, he found at Philadelphia a likewise avid group of civilians and off-duty military men who harbored an interest in the same thing. He rented an airplane and gained permission from the Commandant of the Navy Yard to use an open field at the Philadelphia Navy Yard for test flights. He also joined the Aero Club of Philadelphia, and commenced "selling" Marine Corps aviation to members of the Aero Club, who, through their Washington connections, began to pressure a number of officials, including Major General Commandant William P. Biddle, himself a member of a prominent Philadelphia family.

Cunningham was an avid supporter in the new conceptual Advanced Base Force and though he saw a role for aircraft, requesting assignment to the Navy's flying school at Annapolis. Cunningham served in the Marine guards of New Jersey (BB-16) and North Dakota (BB-29), and the receiving ship USS Lancaster, over the next two years.

In 1911, while he was stationed at the Marine Barracks, Philadelphia Navy Yard, he developed the inspiration to fly. Leasing a plane from a civilian aviator only $25 a month, he experimented in the airplane, nicknamed the "Noisy Nan". He was promoted to the rank and grade of 1st Lieutenant in September 1911. Although the plane never left the ground, his profound faith and love of flying was rewarded. On May 16, 1912, Cunningham received orders and stood detached from duty at the Navy Yard in Philadelphia, and was ordered to the aviation camp the Navy had set up at United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, to learn to fly. He reported six days later, on May 22, 1912, which is recognized as the birthday of Marine Corps aviation. Actual flight training was given at the Burgess Plant at Marblehead, Massachusetts, because only the builders of planes could fly in those days and after two hours and forty minutes of instruction, Cunningham soloed on August 20, 1912. He flew the Curtiss seaplane and became Naval Aviator No. 5, and Smith became Naval Aviator No. 6.

Between October 1912 and July 1913, Cunningham made some 400 flights in the Curtiss B-1, conducting training and testing tactics and aircraft capabilities. In August 1913, Cunningham sought detachment from aviation duty, on the grounds that his fiancйe would not marry him unless he gave up flying. Although assigned duty as assistant quartermaster at the Marine Barracks at the Washington Navy Yard, the first Marine aviator continued to advocate Marine Corps aviation and contribute significantly to its growth.

By November 1913, the Navy Department had assigned Cunningham (and Smith) to return to the Advanced Base School with the understanding that they would create an aviation section for the force. Cunningham performed important reconnaissance roles for the force, which was fully functionable by 1914. Later, he served on a board, headed by Captain Washington I. Chambers, USN, tasked with drawing up a comprehensive plan for the organization of a naval aeronautical service. It was upon the recommendation of that board that the Naval Aeronautical Station at Pensacola, Florida, was established in 1914.

The following February, Cunningham was assigned duty at the Washington Navy Yard, assisting Naval Constructor Holden C. Richardson in working on the D-2 flying boat. Ordered to Pensacola for instruction in April 1915 (his wife apparently having relented in allowing her husband to fly), Cunningham was designated Naval Aviator No. 5 on September 17, 1915.

World War I service

After heading the motor erecting shop at Pensacola, he underwent instruction at the Army Signal Corps Aviation School at San Diego, whence he was assigned to the Commission on Navy Yards and Naval Stations. Cunningham received orders on February 26, 1917, to organize the Aviation Company for the Advanced Base Force, at the Philadelphia Navy Yard. Designated as the commander of this unit, Cunningham soon emerged as de facto director of Marine Corps aviation. He sought, and got, enthusiastic volunteers to become pilots, and soon embarked on a determined campaign to define a mission for land-based marine air. In addition, he served on a joint Army-Navy board that selected sites for naval air stations in seven naval districts and on the east and gulf coasts.

Detailed to Europe to obtain information on British and French aviation practices, he participated in a variety of missions over German lines. Returning to the United States in January 1918, he presented a plan to use Marine aircraft to operate against submarines off the Belgian coast and against submarine bases at Zeebrugge, Ostend, and Bruges.

The Northern Bombing Group emerged from these plans-four landplane squadrons equipped and trained in five months' time. On July 12, 1918, 72 planes, 176 officers and 1,030 enlisted men sailed for France on board the transport DeKalb, arriving at Brest on July 30, 1918. The Marines were sent to the fields at Oye, Le Fresne, and St. Pol, France; and at Hoondschoote, Ghietelles, Varsennaire and Knesselaere, Belgium. Despite shortages of planes, spare parts, and tools, the Marines participated in 43 raids with British and French units, as well as 14 independent raids, and shot down eight enemy aircraft. Planes of the group also dropped 52,000 pounds of bombs, and supplied 2,650 pounds of food in five food-dropping missions to encircled French troops. For his service in organizing and training the first Marine aviation force, Cunningham was awarded the Navy Cross.

Post-war activities

After World War I, Cunningham returned to the United States to become officer-in-charge of Marine Corps aviation, a billet in which he remained until December 26, 1920, when he was detailed to command the First Air Squadron in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic. Ordered thence to general duty at Marine Corps Schools, Quantico, Major Cunningham then served as assistant adjutant and inspector, and then division marine officer and aide on the staff of Commander, Battleship Division 3. On temporary detached duty in Nicaragua from June 1928, he served with the 2nd Brigade of Marines as executive officer of the Western Area at Leon, Nicaragua.

Retirement and last years

Subsequently, becoming executive officer and registrar of the Marine Corps Institute from 1929 to 1931, Cunningham finished up his career as assistant quartermaster at the Marine Barracks, Philadelphia. His health failing, Cunningham retired on August 1, 1935. Promoted to lieutenant colonel while on the retired list, he died at Sarasota, Florida, on May 27, 1939. He is buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Honors

The destroyer USS Alfred A. Cunningham (DD-752) is named in his honor.

In 1965, Cunningham was enshrined in the National Aviation Hall of Fame.

Wednesday, April 18, 2012

67 years ago

Victory in Europe Day - known as V-E Day or VE Day - commemorates 8 May 1945 (in Commonwealth countries; 7 May 1945), the date when the World War II Allies formally accepted the unconditional surrender of the armed forces of Nazi Germany and the end of Adolf Hitler's Third Reich. The formal surrender of the occupying German forces in the Channel Islands was not until 9 May 1945. On 30 April Hitler committed suicide during the Battle of Berlin, and so the surrender of Germany was authorized by his replacement, President of Germany Karl Dönitz. The administration headed by Dönitz was known as the Flensburg government. The act of military surrender was signed on 7 May in Reims, France, and ratified on 8 May in Berlin, Germany.

Celebrations

Upon the defeat of the Nazi Germany army, celebrations erupted throughout the western world. From Moscow to New York, people cheered. In the United Kingdom, more than one million people celebrated in the streets to mark the end of the European part of the war. In London, crowds massed in Trafalgar Square and up The Mall to Buckingham Palace, where King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, accompanied by Prime Minister Winston Churchill, appeared on the balcony of the Palace before the cheering crowds. Princess Elizabeth (the future Queen Elizabeth II) and her sister Princess Margaret were allowed to wander anonymously among the crowds and take part in the celebrations.

In the United States, President Harry Truman, who turned 61 that day, dedicated the victory to the memory of his predecessor, Franklin D. Roosevelt, who had died of a cerebral hemorrhage less than a month earlier, on 12 April. Flags remained at half-mast for the remainder of the 30-day mourning period. Truman said of dedicating the victory to Roosevelt's memory and keeping the flags at half-staff that his only wish was "that Franklin D. Roosevelt had lived to witness this day." Massive celebrations also took place in Chicago, Los Angeles, Miami, and especially in New York City's Times Square. Victory celebrations in Canada were marred by the Halifax Riot.

Monday, April 9, 2012

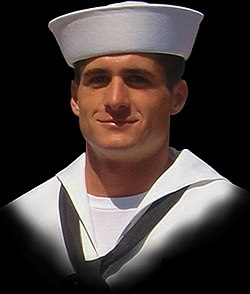

Michael Anthony Monsoor

United States Navy SEAL

Michael Anthony Monsoor (April 5, 1981 - September 29, 2006) was a U.S. Navy SEAL killed during the Iraq War and posthumously received the Medal of Honor. Monsoor enlisted in the United States Navy in 2001 and graduated from Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL training in 2004. After further training he was assigned to Delta Platoon, SEAL Team Three.

Delta Platoon was sent to Iraq in April 2006 and assigned to train Iraqi Army soldiers in Ramadi. Over the next five months, Monsoor and his platoon frequently engaged in combat with insurgent forces. On September 29, 2006 an insurgent threw a grenade onto a rooftop where Monsoor and several other SEAL and Iraqi soldiers were positioned. Monsoor quickly smothered the grenade with his body, absorbing the resulting explosion and saving his comrades from serious injury or death. Monsoor died 30 minutes later from serious wounds caused by the grenade explosion.

On March 31, 2008, the United States Department of Defense confirmed that Michael Monsoor would posthumously receive the Medal of Honor from the President of the United States, George W. Bush. Bush presented the medal to Monsoor's parents on April 8, 2008. In October 2008, United States Secretary of the Navy Donald C. Winter announced that DDG-1001, the second ship in the Zumwalt class of destroyers, would be named Michael Monsoor in his honor.

Early life

Michael was born April 5, 1981 in Long Beach, California, the third of four children born to George and Sally (Boyle) Monsoor. His father George Monsoor also served in the United States military as a Marine. When he was a child Monsoor was afflicted with asthma but strengthened his lungs by racing his siblings in the family's swimming pool. He attended Dr. Walter C. Ralston Intermediate School and Garden Grove High School in Garden Grove, California and played tight-end on the school's football team, graduating in 1999. Monsoor is of Lebanese Christian descent on his father's side and Irish by way of his mother.

Military service

Monsoor enlisted in the United States Navy on March 21, 2001, and attended Basic Training at Recruit Training Command, Great Lakes, Illinois. Upon graduation from basic training, he attended Quartermaster "A" School, and then transferred to Naval Air Station, Sigonella, Italy for a short period of time. He entered the Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL (BUD/S) training and graduated from Class 250 on September 2, 2004 as one of the top performers in his class. After BUD/S, he completed advanced SEAL training courses including parachute training at Basic Airborne School, cold weather combat training in Kodiak, Alaska, and six months of SEAL Qualification Training in Coronado, California graduating in March 2005. The following month, his rating changed from Quartermaster to Master-at-Arms, and he was assigned to Delta Platoon, SEAL Team 3.

During Operation Kentucky Jumper, SEAL Team Three was sent to Ramadi, Iraq in April 2006 and assigned to train Iraqi Army soldiers. As a communicator and machine-gunner on patrols, Monsoor carried 100 pounds (45 kg) of gear in temperatures often exceeding 100 degrees. He took a lead position to protect the platoon from frontal assault and the team was frequently involved in engagements with insurgent fighters. During the first five months of deployment, the team reportedly killed 84 insurgents.

During an engagement on May 9, 2006, Monsoor ran into a street while under continuous insurgent gunfire to rescue an injured comrade. Monsoor was awarded the Silver Star for this action and was also awarded the Bronze Star for his service in Iraq.

On September 29, 2006, Monsoor's platoon engaged four insurgents in a firefight, killing one and injuring another. Anticipating further attacks, Monsoor, three SEAL snipers and three Iraqi Army soldiers took up a rooftop position. Civilians aiding the insurgents blocked off the streets, and a nearby mosque broadcast a message for people to fight against the Americans and the Iraqi soldiers. Monsoor was protecting other SEALs, two of whom were 15 feet away from him. Monsoor's position made him the only SEAL on the rooftop with quick access to an escape route.

A grenade was thrown onto the rooftop by an insurgent on the street below. The grenade hit Monsoor in the chest and fell onto the floor. Immediately, Monsoor yelled "Grenade!" and jumped onto the grenade, covering it with his body. The grenade exploded seconds later and Monsoor's body absorbed most of the force of the blast. Monsoor was severely wounded and although evacuated immediately, he died 30 minutes later. Two other SEALs next to him at the time were injured by the explosion but survived.

Death and burial

Monsoor died September 29, 2006 in Ar Ramadi, Iraq and was described as a "quiet professional" and a "fun-loving guy" by those who knew him. He is buried at Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery in San Diego.

During the funeral, as the coffin was moving from the hearse to the grave site, Navy SEALs were lined up forming a column of twos on both sides of the pallbearers route, with the coffin moving up the center. As the coffin passed each SEAL, they slapped down the gold Trident each had removed from his own uniform and deeply embedded it into the wooden coffin. For nearly 30 minutes the slaps were audible from across the cemetery as nearly every SEAL on the west coast repeated the ceremony.

The display moved many attending the funeral, including U.S. President George W. Bush, who spoke about the incident later during a speech stating: "The procession went on nearly half an hour, and when it was all over, the simple wooden coffin had become a gold-plated memorial to a hero who will never be forgotten.

Honors and awards

Military awards

Medal of Honor

Silver Star

Bronze Star Medal w/ V device

Purple Heat

Medal Combat Action Ribbon

Navy Good Conduct Medal National Defense Service Medal

Iraq Campaign Medal w/ campaign star

Global War on Terrorism Service Medal

Sea Service Deployment Ribbon Navy & Marine Corps Overseas Service Ribbon

NATO Medal for NTM-IRAQ

Marksmanship Medal for Rifle Expert Marksmanship Medal for Pistol Expert

Navy and Marine Corps Parachutist Insignia

Medal of Honor

On March 31, 2008, the United States Department of Defense confirmed that Michael Monsoor would posthumously receive the Medal of Honor from the President of the United States, George W. Bush. Monsoor's parents, Sally and George Monsoor, received the medal on his behalf at an April 8, ceremony at the White House held by the President. Monsoor became the fourth American servicemember and second Navy SEAL - each killed in the line of duty - to receive the United States' highest military award during the War on Terrorism.

Medal of Honor citation

"The President of the United States in the name of The Congress takes pride in presenting the MEDAL OF HONOR posthumously to

MASTER AT ARMS SECOND CLASS, SEA, AIR and LAND

MICHAEL A. MONSOOR

UNITED STATES NAVY

For service as set forth in the following CITATION:

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty while serving as Automatic Weapons Gunner for Naval Special Warfare Task Group Arabian Peninsula, in support of Operation IRAQI FREEDOM on 29 September 2006. As a member of a combined SEAL and Iraqi Army sniper overwatch element, tasked with providing early warning and stand-off protection from a rooftop in an insurgent-held sector of Ar Ramadi, Iraq, Petty Officer Monsoor distinguished himself by his exceptional bravery in the face of grave danger. In the early morning, insurgents prepared to execute a coordinated attack by reconnoitering the area around the element's position. Element snipers thwarted the enemy's initial attempt by eliminating two insurgents. The enemy continued to assault the element, engaging them with a rocket-propelled grenade and small arms fire. As enemy activity increased, Petty Officer Monsoor took position with his machine gun between two teammates on an outcropping of the roof. While the SEALs vigilantly watched for enemy activity, an insurgent threw a hand grenade from an unseen location, which bounced off Petty Officer Monsoor's chest and landed in front of him. Although only he could have escaped the blast, Petty Officer Monsoor chose instead to protect his teammates. Instantly and without regard for his own safety, he threw himself onto the grenade to absorb the force of the explosion with his body, saving the lives of his two teammates. By his undaunted courage, fighting spirit, and unwavering devotion to duty in the face of certain death, Petty Officer Monsoor gallantly gave his life for his country, thereby reflecting great credit upon himself and upholding the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service."

Silver Star citation

"For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action against the enemy as Platoon Machine Gunner in Sea, Air, Land Team THREE (SEAL-3), Naval Special Warfare Task Group Arabian Peninsula, Task Unit Ramadi, in support of Operation IRAQI FREEDOM on 9 May 2006. Petty Officer Monsoor was the Platoon Machine Gunner of an overwatch element, providing security for an Iraqi Army Brigade during counter-insurgency operations. While moving toward extraction, the Iraqi Army and Naval Special Warfare overwatch team received effective enemy automatic weapons fire resulting in one SEAL wounded in action. Immediately, Petty Officer Monsoor, with complete disregard for his own safety, exposed himself to heavy enemy fire in order to provide suppressive fire and fight his way to the wounded SEAL's position. He continued to provide effective suppressive fire while simultaneously dragging the wounded SEAL to safety. Petty Officer Monsoor maintained suppressive fire as the wounded SEAL received tactical casualty treatment to his leg. He also helped load his wounded teammate into a High Mobility Multi-Purpose Wheeled Vehicle for evacuation, then returned to combat. By his bold initiative, undaunted courage, and complete dedication to duty, Petty Officer Monsoor reflected great credit upon himself and upheld the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service."

Bronze Star citation

"For heroic achievement in connection with combat operations against the enemy as Task Unit Ramadi, Iraq, Combat Advisor for Naval Special Warfare Task Group ? Arabian Peninsula in Support of Operation IRAQI FREEDOM from April to September 2006. On 11 different operations, Petty Officer Monsoor exposed himself to heavy enemy fire while shielding his teammates with suppressive fire. He aggressively stabilized each chaotic situation with focused determination and uncanny tactical awareness. Each time insurgents assaulted his team with small arms fire or rocket propelled grenades, he quickly assessed the situation, determined the best course of action to counter the enemy assaults, and implemented his plan to gain the best tactical advantage. His selfless, decisive, heroic actions resulted in 25 enemy killed and saved the lives of his teammates, other Coalition Forces and Iraqi Army soldiers. By his extraordinary guidance, zealous initiative, and total dedication to duty, Petty Officer Monsoor reflected great credit upon himself and upheld the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service."

USS Michael Monsoor (DDG-1001)

In October 2008, United States Secretary of the Navy Donald C. Winter announced that the second ship in the Zumwalt-class of destroyers would be named USS Michael Monsoor (DDG-1001) in honor of Petty Officer Monsoor.

Other honors

In 2011, United States Department of Veterans Affairs honored Monsoor by naming one of the first three named streets at Miramar National Cemetary after him.

United States Navy SEAL

Michael Anthony Monsoor (April 5, 1981 - September 29, 2006) was a U.S. Navy SEAL killed during the Iraq War and posthumously received the Medal of Honor. Monsoor enlisted in the United States Navy in 2001 and graduated from Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL training in 2004. After further training he was assigned to Delta Platoon, SEAL Team Three.

Delta Platoon was sent to Iraq in April 2006 and assigned to train Iraqi Army soldiers in Ramadi. Over the next five months, Monsoor and his platoon frequently engaged in combat with insurgent forces. On September 29, 2006 an insurgent threw a grenade onto a rooftop where Monsoor and several other SEAL and Iraqi soldiers were positioned. Monsoor quickly smothered the grenade with his body, absorbing the resulting explosion and saving his comrades from serious injury or death. Monsoor died 30 minutes later from serious wounds caused by the grenade explosion.

On March 31, 2008, the United States Department of Defense confirmed that Michael Monsoor would posthumously receive the Medal of Honor from the President of the United States, George W. Bush. Bush presented the medal to Monsoor's parents on April 8, 2008. In October 2008, United States Secretary of the Navy Donald C. Winter announced that DDG-1001, the second ship in the Zumwalt class of destroyers, would be named Michael Monsoor in his honor.

Early life

Michael was born April 5, 1981 in Long Beach, California, the third of four children born to George and Sally (Boyle) Monsoor. His father George Monsoor also served in the United States military as a Marine. When he was a child Monsoor was afflicted with asthma but strengthened his lungs by racing his siblings in the family's swimming pool. He attended Dr. Walter C. Ralston Intermediate School and Garden Grove High School in Garden Grove, California and played tight-end on the school's football team, graduating in 1999. Monsoor is of Lebanese Christian descent on his father's side and Irish by way of his mother.

Military service

Monsoor enlisted in the United States Navy on March 21, 2001, and attended Basic Training at Recruit Training Command, Great Lakes, Illinois. Upon graduation from basic training, he attended Quartermaster "A" School, and then transferred to Naval Air Station, Sigonella, Italy for a short period of time. He entered the Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL (BUD/S) training and graduated from Class 250 on September 2, 2004 as one of the top performers in his class. After BUD/S, he completed advanced SEAL training courses including parachute training at Basic Airborne School, cold weather combat training in Kodiak, Alaska, and six months of SEAL Qualification Training in Coronado, California graduating in March 2005. The following month, his rating changed from Quartermaster to Master-at-Arms, and he was assigned to Delta Platoon, SEAL Team 3.

During Operation Kentucky Jumper, SEAL Team Three was sent to Ramadi, Iraq in April 2006 and assigned to train Iraqi Army soldiers. As a communicator and machine-gunner on patrols, Monsoor carried 100 pounds (45 kg) of gear in temperatures often exceeding 100 degrees. He took a lead position to protect the platoon from frontal assault and the team was frequently involved in engagements with insurgent fighters. During the first five months of deployment, the team reportedly killed 84 insurgents.

During an engagement on May 9, 2006, Monsoor ran into a street while under continuous insurgent gunfire to rescue an injured comrade. Monsoor was awarded the Silver Star for this action and was also awarded the Bronze Star for his service in Iraq.

On September 29, 2006, Monsoor's platoon engaged four insurgents in a firefight, killing one and injuring another. Anticipating further attacks, Monsoor, three SEAL snipers and three Iraqi Army soldiers took up a rooftop position. Civilians aiding the insurgents blocked off the streets, and a nearby mosque broadcast a message for people to fight against the Americans and the Iraqi soldiers. Monsoor was protecting other SEALs, two of whom were 15 feet away from him. Monsoor's position made him the only SEAL on the rooftop with quick access to an escape route.

A grenade was thrown onto the rooftop by an insurgent on the street below. The grenade hit Monsoor in the chest and fell onto the floor. Immediately, Monsoor yelled "Grenade!" and jumped onto the grenade, covering it with his body. The grenade exploded seconds later and Monsoor's body absorbed most of the force of the blast. Monsoor was severely wounded and although evacuated immediately, he died 30 minutes later. Two other SEALs next to him at the time were injured by the explosion but survived.

Death and burial

Monsoor died September 29, 2006 in Ar Ramadi, Iraq and was described as a "quiet professional" and a "fun-loving guy" by those who knew him. He is buried at Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery in San Diego.

During the funeral, as the coffin was moving from the hearse to the grave site, Navy SEALs were lined up forming a column of twos on both sides of the pallbearers route, with the coffin moving up the center. As the coffin passed each SEAL, they slapped down the gold Trident each had removed from his own uniform and deeply embedded it into the wooden coffin. For nearly 30 minutes the slaps were audible from across the cemetery as nearly every SEAL on the west coast repeated the ceremony.

The display moved many attending the funeral, including U.S. President George W. Bush, who spoke about the incident later during a speech stating: "The procession went on nearly half an hour, and when it was all over, the simple wooden coffin had become a gold-plated memorial to a hero who will never be forgotten.

Honors and awards

Military awards

Medal of Honor

Silver Star

Bronze Star Medal w/ V device

Purple Heat

Medal Combat Action Ribbon

Navy Good Conduct Medal National Defense Service Medal

Iraq Campaign Medal w/ campaign star

Global War on Terrorism Service Medal

Sea Service Deployment Ribbon Navy & Marine Corps Overseas Service Ribbon

NATO Medal for NTM-IRAQ

Marksmanship Medal for Rifle Expert Marksmanship Medal for Pistol Expert

Navy and Marine Corps Parachutist Insignia

Medal of Honor

On March 31, 2008, the United States Department of Defense confirmed that Michael Monsoor would posthumously receive the Medal of Honor from the President of the United States, George W. Bush. Monsoor's parents, Sally and George Monsoor, received the medal on his behalf at an April 8, ceremony at the White House held by the President. Monsoor became the fourth American servicemember and second Navy SEAL - each killed in the line of duty - to receive the United States' highest military award during the War on Terrorism.

Medal of Honor citation

"The President of the United States in the name of The Congress takes pride in presenting the MEDAL OF HONOR posthumously to

MASTER AT ARMS SECOND CLASS, SEA, AIR and LAND

MICHAEL A. MONSOOR

UNITED STATES NAVY

For service as set forth in the following CITATION:

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty while serving as Automatic Weapons Gunner for Naval Special Warfare Task Group Arabian Peninsula, in support of Operation IRAQI FREEDOM on 29 September 2006. As a member of a combined SEAL and Iraqi Army sniper overwatch element, tasked with providing early warning and stand-off protection from a rooftop in an insurgent-held sector of Ar Ramadi, Iraq, Petty Officer Monsoor distinguished himself by his exceptional bravery in the face of grave danger. In the early morning, insurgents prepared to execute a coordinated attack by reconnoitering the area around the element's position. Element snipers thwarted the enemy's initial attempt by eliminating two insurgents. The enemy continued to assault the element, engaging them with a rocket-propelled grenade and small arms fire. As enemy activity increased, Petty Officer Monsoor took position with his machine gun between two teammates on an outcropping of the roof. While the SEALs vigilantly watched for enemy activity, an insurgent threw a hand grenade from an unseen location, which bounced off Petty Officer Monsoor's chest and landed in front of him. Although only he could have escaped the blast, Petty Officer Monsoor chose instead to protect his teammates. Instantly and without regard for his own safety, he threw himself onto the grenade to absorb the force of the explosion with his body, saving the lives of his two teammates. By his undaunted courage, fighting spirit, and unwavering devotion to duty in the face of certain death, Petty Officer Monsoor gallantly gave his life for his country, thereby reflecting great credit upon himself and upholding the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service."

Silver Star citation

"For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action against the enemy as Platoon Machine Gunner in Sea, Air, Land Team THREE (SEAL-3), Naval Special Warfare Task Group Arabian Peninsula, Task Unit Ramadi, in support of Operation IRAQI FREEDOM on 9 May 2006. Petty Officer Monsoor was the Platoon Machine Gunner of an overwatch element, providing security for an Iraqi Army Brigade during counter-insurgency operations. While moving toward extraction, the Iraqi Army and Naval Special Warfare overwatch team received effective enemy automatic weapons fire resulting in one SEAL wounded in action. Immediately, Petty Officer Monsoor, with complete disregard for his own safety, exposed himself to heavy enemy fire in order to provide suppressive fire and fight his way to the wounded SEAL's position. He continued to provide effective suppressive fire while simultaneously dragging the wounded SEAL to safety. Petty Officer Monsoor maintained suppressive fire as the wounded SEAL received tactical casualty treatment to his leg. He also helped load his wounded teammate into a High Mobility Multi-Purpose Wheeled Vehicle for evacuation, then returned to combat. By his bold initiative, undaunted courage, and complete dedication to duty, Petty Officer Monsoor reflected great credit upon himself and upheld the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service."

Bronze Star citation

"For heroic achievement in connection with combat operations against the enemy as Task Unit Ramadi, Iraq, Combat Advisor for Naval Special Warfare Task Group ? Arabian Peninsula in Support of Operation IRAQI FREEDOM from April to September 2006. On 11 different operations, Petty Officer Monsoor exposed himself to heavy enemy fire while shielding his teammates with suppressive fire. He aggressively stabilized each chaotic situation with focused determination and uncanny tactical awareness. Each time insurgents assaulted his team with small arms fire or rocket propelled grenades, he quickly assessed the situation, determined the best course of action to counter the enemy assaults, and implemented his plan to gain the best tactical advantage. His selfless, decisive, heroic actions resulted in 25 enemy killed and saved the lives of his teammates, other Coalition Forces and Iraqi Army soldiers. By his extraordinary guidance, zealous initiative, and total dedication to duty, Petty Officer Monsoor reflected great credit upon himself and upheld the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service."

USS Michael Monsoor (DDG-1001)

In October 2008, United States Secretary of the Navy Donald C. Winter announced that the second ship in the Zumwalt-class of destroyers would be named USS Michael Monsoor (DDG-1001) in honor of Petty Officer Monsoor.

Other honors

In 2011, United States Department of Veterans Affairs honored Monsoor by naming one of the first three named streets at Miramar National Cemetary after him.

Thursday, April 5, 2012

EASTER

According to Christians around the world, Easter is a day set aside to commemorate Jesus' resurrection from the dead. But the history of Easter is more complicated than that. The name of the holiday is derived from the name of an ancient, pagan goddess, Eastre, sometimes spelled Eostre. Eastre was the goddess of spring and worshipped by the Teutonic tribes that the early Christians ministered to.

At this point, the history of Easter becomes a little complicated. The early missionaries, seeking to convert the people of the Teutonic tribes, adopted the celebration of Eastre's festival as their own. Since the festival fell around the same time as the Christian's memorial of Jesus' resurrection, the missionaries simply substituted one holiday for another. This allowed the new converts to continue their tradition, but its meaning and purpose had changed.

The history of Easter continued to be complex as the actual date of the celebration was never fully established. Some linked the memorial to the ancient Hebrew calendar's celebration of Passover. Others linked the date to the spring equinox. Finally, in 325 A.D. Emperor Constantine met with other church leaders and together they decreed that Easter would fall on the first Sunday after the first full moon after the spring equinox. However, the controversy over the holiday's date continues with some the Eastern Orthodox Churches still celebrating it at the end of Passover week.

The history of Easter wouldn't be complete without mention of the Easter Bunny and Easter Eggs. Both of these common symbols of Easter are derived from ancient, pagan traditions. Eastre's pagan symbol was the rabbit or hare. The giving and receiving of eggs was also a common tradition in the Teutonic tribes, eggs symbolizing rebirth and renewal.

With or without the Easter Bunny, Easter today, means victory over death for millions of Christians around the world. For it was on this day in the history of Easter, that Jesus conquered death and rose again, bringing light, love, and life to the world forever.

According to Christians around the world, Easter is a day set aside to commemorate Jesus' resurrection from the dead. But the history of Easter is more complicated than that. The name of the holiday is derived from the name of an ancient, pagan goddess, Eastre, sometimes spelled Eostre. Eastre was the goddess of spring and worshipped by the Teutonic tribes that the early Christians ministered to.

At this point, the history of Easter becomes a little complicated. The early missionaries, seeking to convert the people of the Teutonic tribes, adopted the celebration of Eastre's festival as their own. Since the festival fell around the same time as the Christian's memorial of Jesus' resurrection, the missionaries simply substituted one holiday for another. This allowed the new converts to continue their tradition, but its meaning and purpose had changed.

The history of Easter continued to be complex as the actual date of the celebration was never fully established. Some linked the memorial to the ancient Hebrew calendar's celebration of Passover. Others linked the date to the spring equinox. Finally, in 325 A.D. Emperor Constantine met with other church leaders and together they decreed that Easter would fall on the first Sunday after the first full moon after the spring equinox. However, the controversy over the holiday's date continues with some the Eastern Orthodox Churches still celebrating it at the end of Passover week.

The history of Easter wouldn't be complete without mention of the Easter Bunny and Easter Eggs. Both of these common symbols of Easter are derived from ancient, pagan traditions. Eastre's pagan symbol was the rabbit or hare. The giving and receiving of eggs was also a common tradition in the Teutonic tribes, eggs symbolizing rebirth and renewal.

With or without the Easter Bunny, Easter today, means victory over death for millions of Christians around the world. For it was on this day in the history of Easter, that Jesus conquered death and rose again, bringing light, love, and life to the world forever.

Monday, April 2, 2012

Saddam Hussein

Firdos Square statue destruction

The destruction of the Firdos Square statue was a staged event in the 2003 Invasion of Iraq and marked the symbolic end of the Battle of Baghdad. It is an instance of iconoclasm.

Meaning

In April 2002, the 12-meter (39 ft) statue was erected in honor of the 65th birthday of Saddam Hussein.

On April 9, 2003, the statue in Baghdad's Firdos Square, directly in front of the Palestine Hotel where the world's journalists had been quartered, was toppled by a U.S. M88 armored recovery vehicle surrounded by hundreds of celebrating Iraqis, who had been attempting to pull down the statue earlier with little success. One such futile attempt by sledgehammer wielding weightlifter Kadhem Sharif particularly caught media attention. Some of the Iraqis flagged down the M88 and convinced the Marines operating it to tie a cable to the statue and start pulling it down. Eventually the M88 was able to topple the statue which was jumped and stomped upon by Iraqi citizens who then decapitated the head of the statue and dragged it through the streets of the city hitting it with their shoes. The destruction of the statue was shown live on cable news networks as it happened and made the front pages of newspapers and covers of magazines all over the world - symbolizing the fall of the Hussein government. The images of the statue destruction provided a clear refutation of Information Minister Muhammad Saeed al-Sahhaf's reports that Iraq had been winning the war.

A green, abstract sculpture by Bassem Hamad al-Dawiri now stands on the site of the former statue.

Flags

Before the statue was toppled, Marine Corporal Edward Chin of 1st Tank Battalion, 1st Marine Division (attached to 3rd Battalion 4th Marines) climbed the ladder and placed an American flag over the statue's face. An Iraqi flag was then placed over the statue.

Event possibly staged

The event was widely publicized, but allegations that it had been staged were soon published. One picture from the event, published in the London Evening Standard, was allegedly cropped to suggest a larger crowd. A report by the Los Angeles Times stated it was an unnamed Marine colonel, not Iraqi civilians who had decided to topple the statue; and that a quick-thinking Army psychological operations team then used loudspeakers to encourage Iraqi civilians to assist and made it all appear spontaneous and Iraqi-inspired. According to Tim Brown at Globalsecurity.org: "It was not completely stage-managed from Washington, DC but it was not exactly a spontaneous Iraqi operation."

The 2004 film Control Room deals with the incident in depth and indicated that the overall impression of Al Jazeera reporters was that it was staged. The Marines present at the time, 3rd Battalion 4th Marines as well as 1st Tank Battalion, maintain that the scene was not staged other than the assistance they provided.

Firdos Square statue destruction

The destruction of the Firdos Square statue was a staged event in the 2003 Invasion of Iraq and marked the symbolic end of the Battle of Baghdad. It is an instance of iconoclasm.

Meaning

In April 2002, the 12-meter (39 ft) statue was erected in honor of the 65th birthday of Saddam Hussein.

On April 9, 2003, the statue in Baghdad's Firdos Square, directly in front of the Palestine Hotel where the world's journalists had been quartered, was toppled by a U.S. M88 armored recovery vehicle surrounded by hundreds of celebrating Iraqis, who had been attempting to pull down the statue earlier with little success. One such futile attempt by sledgehammer wielding weightlifter Kadhem Sharif particularly caught media attention. Some of the Iraqis flagged down the M88 and convinced the Marines operating it to tie a cable to the statue and start pulling it down. Eventually the M88 was able to topple the statue which was jumped and stomped upon by Iraqi citizens who then decapitated the head of the statue and dragged it through the streets of the city hitting it with their shoes. The destruction of the statue was shown live on cable news networks as it happened and made the front pages of newspapers and covers of magazines all over the world - symbolizing the fall of the Hussein government. The images of the statue destruction provided a clear refutation of Information Minister Muhammad Saeed al-Sahhaf's reports that Iraq had been winning the war.

A green, abstract sculpture by Bassem Hamad al-Dawiri now stands on the site of the former statue.

Flags

Before the statue was toppled, Marine Corporal Edward Chin of 1st Tank Battalion, 1st Marine Division (attached to 3rd Battalion 4th Marines) climbed the ladder and placed an American flag over the statue's face. An Iraqi flag was then placed over the statue.

Event possibly staged

The event was widely publicized, but allegations that it had been staged were soon published. One picture from the event, published in the London Evening Standard, was allegedly cropped to suggest a larger crowd. A report by the Los Angeles Times stated it was an unnamed Marine colonel, not Iraqi civilians who had decided to topple the statue; and that a quick-thinking Army psychological operations team then used loudspeakers to encourage Iraqi civilians to assist and made it all appear spontaneous and Iraqi-inspired. According to Tim Brown at Globalsecurity.org: "It was not completely stage-managed from Washington, DC but it was not exactly a spontaneous Iraqi operation."

The 2004 film Control Room deals with the incident in depth and indicated that the overall impression of Al Jazeera reporters was that it was staged. The Marines present at the time, 3rd Battalion 4th Marines as well as 1st Tank Battalion, maintain that the scene was not staged other than the assistance they provided.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)