Battle of Belleau Wood

Battle of Belleau Wood

United States Marine Corps - World War IThe Battle of Belleau Wood (1 June 1918 - 26 June 1918) occurred during the German 1918 Spring Offensive in World War I, near the Marne River in France. The battle was fought between the U.S. Second (under the command of Major General Omar Bundy) and Third Divisions and an assortment of German units including elements from the 237th, 10th, 197th, 87th, and 28th Divisions.

Background

In March 1918, with nearly 50 additional divisions freed by the Russian surrender on the Eastern Front, the German Army launched a series of attacks on the Western Front, hoping to defeat the Allies before United States forces could be fully deployed.

In the north, the British 5th Army was virtually destroyed by two major offensive operations, Michael and Georgette around the Somme. A third offensive launched in May against the French between Soissons and Reims, known as the Third Battle of the Aisne, saw the Germans reach the north bank of the Marne river at Chateau-Thierry, 40 miles (64 km) from Paris, on 27 May. Two U.S. Army divisions, the 2nd and the 3rd, were thrown into the Allied effort to stop the Germans. On 31 May, the 3rd Division held the German advance at Chateau-Thierry and the German advance turned right towards Vaux and Belleau Wood.

On 1 June, Chateau-Thierry and Vaux fell, and German troops moved into Belleau Wood. The U.S. 2nd Division, which included a brigade of U.S. Marines, was brought up along the Paris-Metz highway. The 9th Infantry Regiment was placed between the highway and the Marne, while the 6th Marine Regiment was deployed to their left. The 5th Marines and 23rd Infantry regiments were placed in reserve.

Battle

On the evening of 1 June, German forces punched a hole in the French lines to the left of the Marines' position. In response, the U.S. reserve, consisting of the 23rd Infantry regiment, the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines, and an element of the 6th Machine Gun Battalion, conducted a forced march over 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) to plug the gap, which they achieved by dawn. By the night of 2 June, the U.S. forces held a 12 miles (19 km) front line north of the Paris-Metz Highway running through grain fields and scattered woods, from Triangle Farm west to Lucy and then north to Hill 142. The German line opposite ran from Vaux to Bouresches to Belleau.

German advance halted at Belleau Wood

German commanders ordered an advance on Marigny and Lucy through Belleau Wood as part of a major offensive, in which other German troops would cross the Marne River. The commander of the Marine Brigade, Army Gen. James Harbord, countermanding a French order to dig trenches further to the rear, ordered the Marines to "hold where they stand". With bayonets, the Marines dug shallow fighting positions from which they could fight from the prone position. In the afternoon of 3 June, German infantry attacked the Marine positions through the grain fields with bayonets fixed. The Marines waited until the Germans were within 100 yards (91 m) before opening fire with deadly rifle fire which mowed down waves of German infantry and forced the survivors to retreat into the wood.

Having suffered heavy casualties, the Germans dug in along a defensive line from Hill 204, just east of Vaux, to Le Thiolet on the Paris-Metz Highway and northward through Belleau Wood to Torcy. After Marines were repeatedly urged to turn back by retreating French forces, Marine Captain Lloyd W. Williams of the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines uttered the now-famous retort "Retreat? Hell, we just got here."Williams' battalion commander, Maj. Frederic Wise, later claimed he said the famous words.

On 4 June, Maj. Gen. Bundy, commanding the 2nd Division, took command of the American sector of the front. Over the next two days, Marines repelled the continuous German assaults. The 167th French Division arrived, giving Bundy a chance to consolidate his 2,000 yards (1,800 m) of front. Bundy's 3rd brigade held the southern sector of the line, while the Marine Brigade held the north of the line from Triangle Farm.

Attack on Hill 142

At 3:45 on the early morning of 6 June, the Allies planned an attack on the Germans who were preparing their own strike. The French 167th Division attacked to the left of the American line, while the Marines attacked Hill 142 to prevent flanking fire against the French. As part of the second phase, the 2nd Division would capture the ridge overlooking Torcy and Belleau Wood, as well as occupying Belleau Wood. However, the Marines failed to scout the woods. As a consequence, they missed a regiment of German infantry dug in, with a network of machine gun nests and artillery.

At dawn, the Marine 1st Battalion, 5th Marines, commanded by Major Julius Turrill, was to attack Hill 142, but only two companies were in position. The Marines advanced in waves with bayonets fixed across an open wheat field that was continuously swept with German machine gun and artillery fire, and many Marines were cut down. Captain Crowther commanding the 67th Company was killed almost immediately. Captain Hamilton and the 49th Company fought from woods to woods, fighting entrenched Germans and overrunning their objective by 600 yards. At this point, Hamilton had lost all five junior officers, while the 67th had only one officer alive. Hamilton reorganized the two companies, establishing strong points and a defensive line.

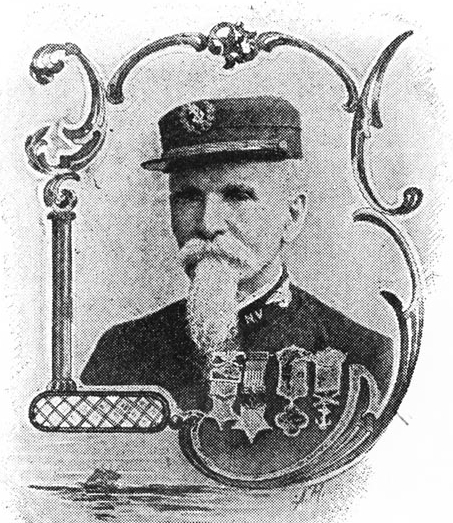

In the German counter-attack, Gunnery Sergeant Ernest A. Janson, who was serving under the name Charles Hoffman, became the first Marine to receive the Medal of Honor in World War I when he repelled an advance of 12 Germans, killing two with his bayonet before the others fled. Gunner Henry Hulbert was also cited for advancing through enemy fire.

The rest of the battalion arrived and went into action. Turrill's flanks lay unprotected and the Marines were exhausting their ammunition rapidly. However by the afternoon the Marines had captured Hill 142, at a cost of nine officers and most of the 325 men of the battalion.

Marines attack Belleau Wood

At 5pm on 6 June, the 3rd Battalion 5th Marines (3/5), commanded by Major Benjamin S. Berry, and the 3rd Battalion 6th Marines (3/6), commanded by Maj. Berton W. Sibley, on their right, advanced from the west into Belleau Wood as part of the second phase of the Allied offensive. Again, the Marines had to advance through a waist-high wheat field into murderous machine gun fire. One of the most famous quotations in Marine Corps lore came during the initial step-off for the battle when Gunnery Sergeant Dan Daly, recipient of two Medals of Honor and who had previously served in the Philippines, Santo Domingo, Haiti, Peking and Vera Cruz, prompted his men of the 73rd Machine Gun company forward with the words: "Come on, you sons of bitches, do you want to live forever?"

The first waves of Marines, advancing in well-disciplined lines, were slaughtered, and Major Berry was wounded in the forearm during the advance. On his right, the Marines of Major Sibley's 3/6 Battalion swept into the southern end of Belleau Wood and encountered heavy machine gun fire, sharpshooters and barbed wire. Soon, Marines and Germans were engaged in heavy hand-to-hand fighting.

The casualties sustained on this day were the highest in Marine Corps history at that point. 31 officers and 1,056 men of the Marine brigade were casualties. However, the Marines now had a foothold in Belleau Wood.

Fighting in Belleau Wood

The battle was now deadlocked. At midnight on 7-8 June, a German attack was stopped cold and an American counter-attack in the morning of 8 June was similarly defeated. Sibley's battalion, having sustained nearly 400 casualties, was relieved by the 1st Battalion, 6th Marines. Major Shearer took over the 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines for the wounded Berry.

On 9 June, an enormous American and French barrage devastated Belleau Wood, turning the formerly attractive hunting preserve into a jungle of shattered trees. The Germans counter-fired into Lucy and Bouresches and reorganized their defenses inside Belleau Wood.

In the morning of 10 June, Maj. Hughes' 1st Battalion, 6th Marines, together with elements of the 6th Machine Gun Battalion attacked north into the wood. Although this attack initially seemed to be succeeding, it was also stopped by machine gun fire. The commander of the 6th Machine Gun Battalion, Maj. Cole, was mortally wounded. Captain Harlan Major, senior captain present with the battalion, took command. The Germans used great quantities of mustard gas. Next, Wise's 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines was ordered to attack the woods from the west, while Hughes continued his advance from the south.

At 4:00 am on 11 June, Wise's men advanced through a thick morning mist towards Belleau Wood, supported by the 23rd and 77th Companies of the 6th Machine Gun Battalion, and were cut to pieces by heavy fire. Platoons were isolated and destroyed by interlocked machine gun fire. It was discovered that the battalion had advanced in the wrong direction. Rather than moving north-east, they had moved directly across the wood's narrow waist. However, they smashed the German southern defensive lines. A German private, whose company had 30 men left out of 120, wrote "We have Americans opposite us who are terribly reckless fellows."

Overall, the woods were attacked by the Marines a total of six times before they could successfully expel the Germans. They fought off parts of five divisions of Germans, often reduced to using only their bayonets or fists in hand-to-hand combat.

On 26 June the 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines, supported by two companies of the 4th Machine Gun Battalion and the 15th Company of the 6th Machine Gun Battalion, made an attack on Belleau Wood, which finally cleared that forest of the enemy. On that day a report was sent out simply stating, "Woods now U.S. Marine Corps entirely," ending one of the bloodiest and most ferocious battles U.S. forces would fight in the war.

After the battle

U.S. forces suffered 9,777 casualties, included 1,811 killed. Many are buried in the nearby Aisne-Marne American Cemetery. There is no clear information on the number of Germans killed, although 1,600 Germans were taken prisoner.

After the battle, the French renamed the wood "Bois de la Brigade de Marine" ("Wood of the Marine Brigade") in honor of the Marines' tenacity. The French government also later awarded the 4th Brigade the Croix de guerre. Belleau Wood is allegedly also where the Marines got their nickname "Teufel Hunden" meaning "Devil Dogs" in poor German (actually "Teufelshunde" in proper German), for the ferocity with which they attacked. An official German report classified the Marines as "vigorous, self-confident, and remarkable marksmen..." General Pershing, Commander of the AEF, even said, "The deadliest weapon in the world is a Marine and his rifle!"

Pershing also said "the Battle of Belleau Wood was for the U.S. the biggest battle since Appomattox and the most considerable engagement American troops had ever had with a foreign enemy."

Legacy

In 1923, an American battle monument was built in Belleau Wood. Army General James. G. Harbord, the commander of the Marines during the battle, was made an honorary Marine. In his address, he summed up the future of the site:

"Now and then, a veteran ... will come here to live again the brave days of that distant June. Here will be raised the altars of patriotism; here will be renewed the vows of sacrifice and consecration to country. Hither will come our countrymen in hours of depression, and even of failure, and take new courage from this shrine of great deeds."

White crosses and Stars of David mark 2,289 graves, 250 for unknown service members, and the names of 1,060 missing men adorn the wall of a memorial chapel. Visitors also stop at the nearby German cemetery where 8,625 men are buried; 4,321 of them"3,847 unknown"rest in a common grave. The German cemetery was established in March 1922, consolidating a number of temporary sites, and includes men killed between the Aisne and the Marne in 1918, along with 70 men who died in 1914 in the First Battle of the Marne.

In New York City, a 0.197-acre (800 m2) triangle at the intersection of 108 Street and 51st Avenue in Queens is dedicated to Marine Pvt. William F. Moore, 47th Company, 2nd Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment.

The Fifth and Sixth Marine Regiments were awarded the French Fourragere for their actions at Belleau Wood.

Two U.S. Navy vessels have been named the USS Belleau Wood (CVL-24 and LHA-3) after the battle.

"Belleau Wood" is a song released by American Country Music artist Garth Brooks. It was the 14th track from his 1997 album Sevens. The song was co-written by Joe Henry and tells the story of opposing forces joining in the singing of Silent Night during the Christmas Truce.

Battle of Belleau Wood

Battle of Belleau Wood