U.S. Marine Corps

Chesty retired from the Corps at Camp Lejeune, N.C. on 1 Nov. 1955. I, Noah, attended his retirement party at the Staff NCO Club.

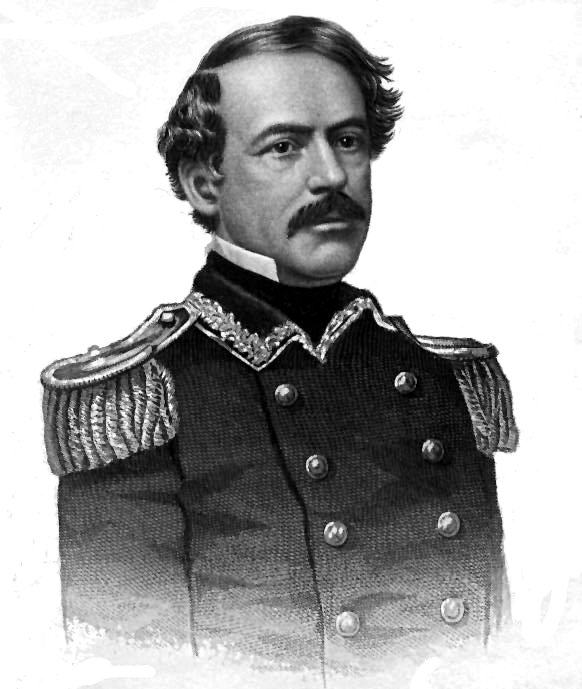

Lieutenant General Lewis "Chesty" Burwell Puller, colorful veteran of the Korean fighting, four World War II campaigns and expeditionary service in China, Nicaragua and Haiti, was one of the most decorated Marines in the Corps, and the only Leatherneck ever to win the Navy Cross five times for heroism and gallantry in action. Promoted to his final rank and placed on the temporary disability retired list 1 November 1955, he died on 11 October 1971 in Hampton, Virginia after a long illness.

The general's last active duty station was Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, where he was commanding the 2d Marine Division when he became seriously ill in August 1954. After that he served as Deputy Camp Commander until his illness forced him to retire.

A Marine officer and enlisted man for 37 years, General Puller served at sea or overseas for all but ten of those years, including a hitch as commander of the "Horse Marines" in China. Excluding medals from foreign governments, he won a total of 14 personal decorations in combat, plus a long list of campaign medals, unit citation ribbons, and other awards. In addition to his Navy Crosses (the next-highest decoration to the Medal of Honor for Naval personnel), he holds its Army equivalent, the Distinguished Service Cross.

He was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross and his fifth Navy Cross for heroism in action as commander of the 1st Marines, 1st Marine Division, during the bitter fight to break out of Korea's Chosin Reservoir area. The latter citation, covering the period from 5-10 December 1950, states in part:

"Fighting continuously in sub-zero weather against a vastly outnumbering hostile force, (the then) Colonel Puller drove off repeated and fanatical enemy attacks upon his Regimental defense sector and supply points. Although the area was frequently covered by grazing machine gun fire and intense artillery and mortar fire, he coolly moved among his troops to insure their correct tactical employment, reinforced the lines as the situation demanded and successfully defended his perimeter, keeping open the main supply routes for the movement of the Division.

During the attack from Koto-ri to Hungman, he expertly utilized his Regiment as the Division rear guard, repelling two fierce enemy assaults which severely threatened the security of the unit, and personally supervised the care and prompt evacuation of all casualties.

By his unflagging determination, he served to inspire his men to heroic efforts in defense of their positions and assured the safety of much valuable equipment which would otherwise have been lost to the enemy. His skilled leadership, superb courage and valiant devotion to duty in the face of overwhelming odds reflect the highest credit upon Colonel Puller and the United States Naval Service."

Serving in Korea from September 1950 to April 1951, the general also earned the Army Silver Star Medal in the Inchon landing, his second Legion of Merit with Combat "V" in the Inchon-Seoul fighting and the early phases of the Chosin Reservoir campaign, and three Air Medals for reconnaissance and liaison flights over enemy territory.

General Puller also fought with the 1st Marine Division in the World War II campaigns on Guadalcanal, Eastern New Guinea, Camp Gloucester and Peleliu, earning his third Navy Cross and the Bronze Star and Purple Heart Medals at Guadalcanal, his fourth Navy Cross at Cape Gloucester, and his first Legion of Merit with Combat "V" at Peleliu. He won his first Navy Cross in November 1930, and his second in September and October 1932, while fighting bandits in Nicaragua.

Born 26 June 1898, at West Point, Virginia, the general attended Virginia Military Institute until enlisting in the Marine Corps in August 1918. He was appointed a Marine Reserve second lieutenant 16 June 1919, but due to the reduction of the Marine Corps after World War I, was placed on inactive duty ten days later. He rejoined the Marines as an enlisted man on the 30th of that month, to serve as an officer in the Gendarmerie d'Haiti, a military force set up in that country under a treaty with the United States. Most of its officers were U.S. Marines, while its enlisted personnel were Haitians.

After almost five years in Haiti, where he saw frequent action against the Caco rebels, General Puller returned to the United States in March 1924. He was commissioned a Marine second lieutenant that same month, and during the next two years, served at the Marine Barracks, Norfolk, Virginia, completed the Basic School at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and served with the 10th Marines at Quantico, Virginia. He was then detailed to duty as a naval aviator at Pensacola, Florida, in February 1926.

In July of that year, the general embarked for a two-year tour of duty at the Marine Barracks, Pearl Harbor. Returning in June 1928, he served at San Diego, California, until he joined the Nicaraguan National Guard Detachment that December. After earning his first Navy Cross in Nicaragua he returned to the United States in July 1931, to enter the Company Officers Course at the Army Infantry School, Fort Benning, Georgia. He completed the course in June 1932, and returned to Nicaragua the following month to begin the tour of duty which brought him his second Navy Cross.

In January 1933, General Puller left Nicaragua for the west coast of the United States. A month later he sailed from San Francisco to join the Marine Detachment of the American Legation at Peiping, China. There, in addition to other duties, he commanded the famed "Horse Marines." Without coming back to the United States he began a tour of sea duty in September 1934, as commanding officer of the Marine Detachment aboard the USS Augusta of the Asiatic Fleet. In June 1936, he returned to the United States to become an instructor in the Basic School at Philadelphia. He left there in May 1939, to serve another years as commander of the Augusta's Marine detachment, and from that ship, joined the 4th Marines at Shanghai, China, in May 1940.

After serving as a battalion executive and commanding officer with the 4th Marines, General Puller sailed for the United States in August 1941, just four months before the attack on Pearl Harbor. In September he took command of the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, 1st Marine Division, at Camp Lejeune. That regiment was detached from the 1st Division in March 1942, and the following month, as part of the 3d Marine Brigade, it sailed for the Pacific theater. The 7th Marines rejoined the 1st Marine Division in September 1942, and General Puller, still commanding its 1st Battalion, went on to earn his third Navy Cross at Guadalcanal.

The action which brought him that medal occurred on the night of 24-25 October 1942. For a desperate three hours his battalion, stretched over a mile-long front, was the only defense between vital Henderson Airfield and a regiment of seasoned Japanese troops. In pouring jungle rain the Japanese smashed repeatedly at his thin line, as General Puller moved up and down its length to encourage his men and direct the defense. After reinforcements arrived he commanded the augmented force until late the next afternoon. The defending Marines suffered less than 70 casualties in the engagement, while 1,400 of the enemy were killed and 17 truckloads of Japanese equipment were recovered by the Americans.

After Guadalcanal the general became executive officer of the 7th Marines. He was fighting in that capacity when he won his forth Navy Cross at Cape Gloucester in January 1944. When the commanders of two battalions were wounded, he took over their units and moved through heavy machine gun and mortar fire to reorganize them for attack, then led them in taking a strongly-fortified enemy position.

In February 1944, General Puller took command of the 1st Marines at Cape Gloucester. After leading that regiment for the remainder of the campaign, he sailed with it for the Russell Islands in April 1944, and went on from there to command it at Peleliu in September and October 1944. He returned to the United States in November 1944, was named executive officer of the Infantry Training Regiment at Camp Lejeune in January 1945, and took command of that regiment the next month.

In August 1946, General Puller became Director of the 8th Marine Corps Reserve District, with headquarters at New Orleans, Louisiana. After that assignment he commended the Marine Barracks at Pearl Harbor until August 1950, when he arrived at Camp Pendleton, California, to re-establish and take command of the 1st Marines, the same regiment he had led at Cape Gloucester and Peleliu.

Landing with the 1st Marines at Inchon, Korea, in September 1950 he continued to head that regiment until January 1951, when he was promoted to brigadier general and named Assistant Commander of the 1st Marine Division. That May he returned to Camp Pendleton to command the newly reactivated 3d Marine Brigade, which was redesignated the 3d Marine Division in January 1952. After that, he was Assistant Division Commander until he took over the Troop Training Unit, Pacific, at Coronado, California, that June. He was promoted to major general in September 1953, and in July 1954, assumed command of the 2d Marine Division at Camp Lejeune. Despite his illness he retained that command until February 1955, when he was appointed Deputy Camp Commander. He served in that capacity until August, when he entered the U.S. Naval Hospital at Camp Lejeune prior to retirement. After his death in October 1971, he was buried in a family plot at the Christi's Church Cemetery, Middlesex County, Virginia.

As already mentioned, the general holds the Navy Cross with Gold Stars in lieu of four additional awards; the Army Distinguished Service Cross; the Army Silver Star Medal; the Legion of Merit with Combat "V" and Gold Star in lieu of a second award; the Bronze Star Medal with Combat "V;" the Air Medal with Gold Stars in lieu of second and third awards; and the Purple Heart Medal. His other medals and decorations include the Presidential Unit Citation Ribbon with four bronze stars; the Marine Corps Good Conduct Medal with one bronze star; the World War I Victory Medal with West Indies clasp; the Haitian Campaign Medal; the Second Nicaraguan Campaign Medal; the Marine Corps Expeditionary Medal with one bronze star; the China Service Medal; the American Defense Service Medal with Base clasp; the American Area Campaign Medal; the Asiatic-Pacific Area Campaign Medal with four bronze stars; the World War II Victory Medal; the National Defense Service Medal; the Korean Service Medal with one silver star in lieu of five bronze stars; the United Nations Service Medal; the Haitian Medaille Militaire; the Nicaraguan Presidential Medal of Merit with Diploma; the Nicaraguan Cross of Valor with Diploma; the Republic of Korea's Ulchi Medal with Gold Star; and the Korean Presidential Unit Citation with Oak Leaf Cluster.

Fix Bayonets

Fix Bayonets