Hugh O'Brian, former Marine

Hugh O'Brian, former Marine

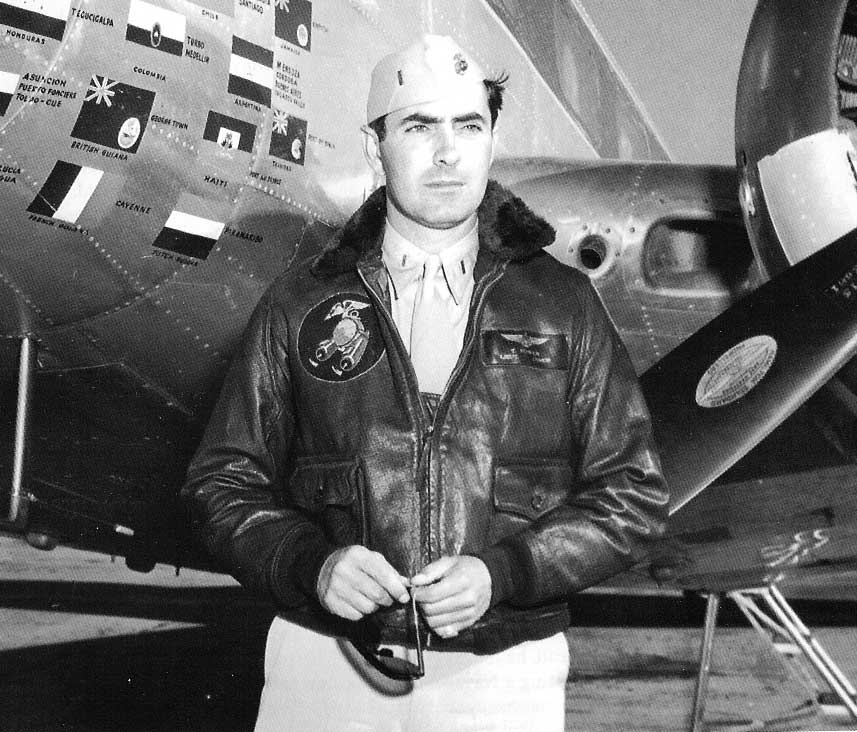

When we think of Hugh O'Brian, we think of him as a actor - that he was. We also think of him as a lawman, Wyatt Earp, that he portrayed on television for several years. However, we never think of him as a former United States Marine. O'Brian enlisted in the Marine Corps at age 17 in 1943. At age 18, he became the youngest (DI) drill instructor in the history of the United States Marine Corps.

Motion picture and television star Hugh O'Brian has mastered his craft across the entire spectrum of show business. But with all his success, he has never lost sight of his civic and philanthropic responsibilities that his chosen field offers to those who choose to use their popularity to motivate others for a worthy cause. He has reinvested his good fortune in many ways to help others, working tirelessly to develop projects to benefit young people.

He is the Founder and Chairman of the Executive Committee of Hugh O'Brian Youth Leadership (HOBY), organized by Hugh in 1958 "to seek out, recognize and develop leadership potential in high school sophomores". HOBY is endowed in perpetuity by Mr. O'Brian's will. In 1964, he also set up the Hugh O'Brian Acting Awards at UCLA, designed to bring recognition to the outstanding young actors and actresses at the University, which was held annually for 25 years.

Born in 1925 in Rochester, New York, Mr. O'Brian's introduction to diversification came early. He attended high school at New Trier in Winnetka, Illinois; Rossevelt Military Academy in Aledd, Ill. and Kemper Military School in Booneville, Missouri. In high school, his sports activities were diversified among football, basketball, wrestling and track, winning letters in all four sports. After a semester at the University of Cincinnati with studies charted toward a law career, Mr. O'Brian, at 17, enlisted in the Marine Corps in 1943. He became the youngest drill instructor in the Marine Corps' history at age 18, and during his four-year service won a coveted Marine Fleet appointment to The United States Naval Academy. After passing the entrance exams, he declined the appointment at the end of World War II, intending to enroll at Yale to study law.

After serving four years, and receiving his honorable discharge from the Marine Corps in 1947, Mr. O'Brian went to Los Angeles where he planned to earn money for his Yale tuition. He met Ruth Roman and Linda Christian, very successful actresses at the time, who introduced him to a "little theatre" group. When a leading man became ill, Mr. O'Brian agreed to substitute. Originally, he felt the experience might be helpful in his law career; however, he got such good reviews in Somerset Maugham's play "Home and Beauty," that he decided to enroll at UCLA, and continue his little theater appearances as an avocation while continuing his quest for a college education. About a year later in 1948, Ida Lupino saw one of his performances and signed him to portray his first starring role in the film "Young Lovers" which Ms. Lupino directed. This brought him a contract with Universal Studios. During his first year under contract he enrolled at Los Angeles City College and managed to amass 17 college credits in addition to making five pictures at Universal.

Mr. O'Brian left Universal after three years to star in three films for 20th Century Fox, "There's No Business Like Show Business", "Broken Lance" and "White Feather", along with numerous television shows. The "big break" in his career came in 1954, when he was chosen to portray the legendary lawman Wyatt Earp on TV. Shortly after the series debuted in September, 1955 as the "first adult western", it became the top-rated show on TV and Mr. O'Brian became a much-discussed talent. During its seven-year run, "Wyatt Earp" always placed in the top five T.V. shows in the nation. In 1972-73 he starred in another TV series "Search".

Mr. O'Brian has also had an illustrious career in the theatre. He starred on Broadway in "Destry Rides Again," "First Love," and in the first Broadway revival of "Guys and Dolls." He also starred in the national company of "The Music Man", "Mr. Roberts", "Cactus Flower," "The Odd Couple," "The Tender Trap," "A Thousand Clowns," and "Plaza Suite." He has guest-starred on numerous television shows including the Today Show, the Larry King and Jim Bohannan Shows, Charlie Rose's Nightwatch and The Pat Sajak Show.

More recent TV/film credits include "The Shootist" (John Wayne's last film), "Killer Force," "Game of Death," "Twins" (with Arnold Schwartzenegger), and numerous appearances on TV's "Fantasy Island," "Love Boat," "Paradise," "Gunsmoke II", "Murder, She Wrote", "L.A. Law", and a Kenny Rogers Gambler IV movie "The Luck of the Draw: The Gambler Returns", a 1994 return to the famous Wyatt Earp role, "Wyatt Earp: Return to Tombstone", received great reviews and the honor of being the highest rated TV show of the week.

In 1958, Mr. O'Brian was privileged to spend nine inspirational days with Nobel Laureate and great humanitarian Dr. Albert Schweitzer, at his clinic in Africa. Dr. Schweitzer's strong belief that "the most important thing in education is to teach young people to think for themselves" impressed O'Brian. Two weeks after his return to the United States, he put Schweitzer's words into action by forming The Hugh O'Brian Youth Leadership (HOBY). Its format for motivation is simple: bring a select group of high school sophomores with demonstrated leadership abilities together with a group of distinguished leaders in business, education, government and the professions, and let the two interact. Using a question-and-answer format, the young people selected annually by over 14,500 public and private high school to attend a HOBY Leadership Development Seminar held each spring in their state get a realistic look at what makes America's Incentive System work, thus better enabling them "to think for themselves."

HOBY Leadership Development Seminars take place in all 50 states (38 states hold two to five seminars per state, because of the large number of schools in that state), as well as in Canada, China, Israel and Mexico. All public and private high schools in the United States receive HOBY's nomination materials by the end of September each year. All lOth-graders are eligible, and encouraged to apply. More than 14,500 "outstanding" high school sophomores, selected to represent as many schools, will attend these three to four day educational seminars annually. All HOBY programs are coordinated by volunteers. Service organizations such as the Kiwanis, General Foundation of Women's Clubs, the National Management Association, Optimists, Lion's Club and Jaycees are the backbone of this volunteer effort. Mr. O'Brian himself sets a positive example by donating 70 hours a week or more to HOBY.

One boy and girl is selected from each of the local 90 HOBY Leadership Seminar sites held each spring to represent their state at HOBY's "Superbowl", the eight-day, all-expense paid World Leadership Congress (WLC), which is held annually in a major U.S. city, and is coordinated by a prestigious university. In addition, outstanding 10th graders from 45 countries are selected to represent their part of the world committee to attend the annual HOBY WLC program. The cultural differences that exist between countries of the world are explored in friendship by the American sophomores and their international counterparts. The HOBY experience is truly an inspirational event of a lifetime for these young future leaders.

HOBY is a non-profit organization and is funded solely through the private sector. It does not seek support from any government source. HOBY is one of America's best examples of a "private sector" initiative.

HOBY's goal is not to teach these future leaders "what to think, not how to think", and what the thinking process is. In essence, HOBY is a dream, which through Mr. 0'Brian's dedication and vision, along with the steadfast efforts of his army of 4,000 dedicated volunteer supporters, has become a reality to benefit mankind. Following is Hugh O'Brian's credo:

The Freedom to Choose:

"I do NOT believe we are all born equal. Created equal in the eyes of God, yes, but physical and emotional differences, parental guidelines, varying environments, being in the right place at the right time, all play a role in enhancing or limiting an individual's development. But I DO believe every man and woman, if given the opportunity and encouragement to recognize their potential, regardless of background, has the freedom to choose in our world. Will an individual be a taker or a giver in life? Will that person be satisfied merely to exist or seek a meaningful purpose? Will he or she dare to dream the impossible dream?

I believe every person is created as the steward of his or her own destiny with great power for a specific purpose, to share with others, through service, a reverence for life in a spirit of love."

In 1972, Mr. 0'Brian was awarded one of the nation's highest honors, the Freedom Through Knowledge Award, sponsored by the National Space Club in association with NASA.

In 1973, he was honored by the American Academy of Achievement.

In 1974, he was awarded the George Washington Honor Medal, highest award of the Freedom Foundation at Valley Forge, as well as the coveted Globe and Anchor Award from the Marine Corps.

In 1976, the Veterans of Foreign Wars honored him with an award. He is the recipient of the AMVETS Silver Helmet Award, and in 1983, the National Society of Fund Raising Executives (NSFRE) honored him with their premier award for overall philanthropic excellence as a volunteer, fundraiser and philanthropist. This is the only time one individual has received the award in all three categories. Notre Dame honored him with the first "Pat 0'Brian Memorial Award" in 1984. That same year, The Family Counseling Service honored Mr. O'Brian with its first National Family of Man Award.

In 1989, he received the 60th Annual American Education Award presented by the American Association of School Administrators. This award is the oldest and most prestigious award that the education profession bestows.

On June 2, 1990, the Los Angeles Business Council awarded Mr. O'Brian its sixth Lifetime Achievement Award, in recognition of outstanding achievement working within the framework of the American Free Enterprise System.

In 1992, Mr. O'Brian was inducted into the Great Western Performers Hall of Fame, and in 1993, Mr. O'Brian was awarded the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Franklin Mint.

In 1994, Mr. O'Brian was awarded the Freedoms Foundation's Private Enterprise Exemplar medal, in 1995 the American Celtic Globe Humanitarian Award from the Ireland Chamber of Commerce, in 1995 the Epsilon Sigma Alpha (ESA, Int.) Vision Award, and in 1997 the KNX Newsradio Man of the Year Award and the Central City Association of Los Angeles' Treasures of Los Angeles Award.

In 1998, Mr. O'Brian was given the highest civilian honor from the United States Department of the Navy, the Meritorious Public Service Citation. He was also one of the year 2000 recipients of the National Ethnic Coalition of Organizations Foundation (NECO) Ellis Island Medal of Honor Award. In March, 2002, he will receive the Distinguished Service Award, the highest award given by NAASP/teh National Association of Secondary School Principals.

Mr. 0'Brian has been awarded honorary degrees by seven prestigious institutions of higher learning. He has received honorary Doctorates of Humane Letters from Saint Mary of the Plains College in Kansas,Lebanon Valley College in Pennsylvania, Bloomsburg University in Bloomsburg, Pennsylvania and Green Mountain College, Poultney, Vermont, as well as an honorary Doctor of Laws degree from Saint John's University in New York. In the summer of 1987, Mr. O'Brian was presented with an honorary Doctor of Public Services degree from the University of Denver, and in the summer of 2000, her was presented with an honorary Doctor of Public Service from The George Washington University in Washington, D.C.. Each university honored Mr. 0'Brian for the outstanding work he has undertaken on behalf of youth throughout the United States and the world.

Mr. O'Brian lives in a hilltop home overlooking Beverly Hills. Diverse as ever, his sporting activities include sailing, scuba diving and swimming.

General John A. Lejeune, USMC

General John A. Lejeune, USMC