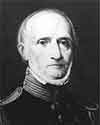

Henry L. Hulbert

Henry L. Hulbert

Marine GunnerBorn at Kingston-upon-Hull, England, January 12, 1867, he was awarded the Medal of Honor for service in the Philippine Insurrection where he served as Private, United States Marine Corps near Samoa, Philippines, on April 1, 1899. Other Navy award: Navy Cross.

Wounded in his regiment's first major engagement, at Belleau Wood on June 6, 1918, Gunner Hulbert was twice cited in official orders for acts of bravery. On one occasion, armed only with a rifle, he single-handedly attacked German machine-gun positions and, as the citation read, "left seven of the enemy dead and put the remainder to flight." The second citation commended him for continuing to lead his platoon in attacks that routed the defenders of a series of strong points despite being painfully wounded himself.

The platoon leader who was old enough to be the father of the men he led, whose stamina and endurance were the envy of men half his age, was not quite finished. A third act of heroism led him to be decorated with the Distinguished Service Cross, one of the first Marines to be so recognized.

In his official report of the monthlong fighting in Belleau Wood, Army Major General Omar L. Bundy, commanding general of the 2d Division, United States Regular, in which the 5th Marines served as part of the famed Marine Brigade, singled out Hulbert, "for his extraordinary heroism in leading attacks against enemy positions on June 6th." General Bundy concluded, "No one could have rendered more valuable service than Gunner Hulbert."

General Bundy was not alone in his praise. Captain George K. Shuler, USMC, wrote, "I should be most glad to have Gunner Hulbert under me in any capacity, and should he through good fortune be promoted over me I should be most happy to serve under his command."

Lieutenant W. T. Galliford, himself a winner of the Distinguished Service Cross, remarked, "If the Fifth Regiment goes over the top, I want to go with Mister Hulbert."

General John J. Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Force, personally recommended that Hulbert be directly commissioned as a Captain.

Heroism under fire at Soissons, an action in which he was again wounded, saw Gunner Hulbert cited for bravery yet again, commissioned a Second Lieutenant and immediately promoted to First Lieutenant. But the trail ahead of him was growing short. At Blanc Mont Ridge on October 4, 1918, the Second Division's bloodiest single day of the war, it ended.

Approved by the Secretary of the Navy for promotion to the grade of Captain, Henry Lewis Hulbert, up front as usual, was struck down by an unknown German machine-gunner. John W. Thomason saw him fall and noted the peaceful look upon his face. He was posthumously awarded the Navy Cross and cited for bravery a fourth time. The French government bestowed the Croix de Guerre Order of the Army upon this "most gallant soldier."

Britannia's son, who gave his life for his adopted land, rests today in Virginia's Arlington National Cemetery. His name is among those inscribed on the Peace Cross at Bladensburg, Maryland, erected in 1919 to honor the memory of the men from Prince George's County who died in the Great War.

But the story of Henry Lewis Hulbert did not end with his death in France. On June 28, 1919, Victoria C. Hulbert, the widow of this inspirational Marine, christened the destroyer USS Henry L. Hulbert (DD-342) when it was launched at Norfolk, Virginia. Commissioned and put into service in 1920, Hulbert served continually on the Asiatic Station until 1929 when she returned to American waters, remaining there until she was decommissioned in 1934. Recalled to service in 1940, Hulbert was assigned to the Pacific Fleet and on December 7, 1941, was moored at Berth D-3, Submarine Base, Pearl Harbor, territory of Hawaii. While Hulbert's whaleboats rescued seamen from stricken ships along Battleship Row, her .50-caliber antiaircraft battery brought down a Japanese torpedo bomber and damaged two others. The ship continued to serve in the Central and North Pacific until she was taken to Philadelphia and decommissioned for the last time in November 1945. In 1946, USS Henry L. Hulbert was stricken from the Navy List and sold for scrap.

In the cold, drizzling pre-dawn dark of Oct. 4, 1918, the 5th Marines passed through the ranks of its brothers in the 6th Marines to continue the attack against the key German strong point of Blanc Mont Ridge in the Champagne country of France. It was a gloomy, brooding place, littered with the wreckage of the previous day's fighting, American, French and German dead all intermingled. A tall Texas Marine in Major George Hamilton's 1st Battalion, Lieutenant John W. Thomason, thought it an evil place, made for calamities. Private Elton Mackin, one of Hamilton's battalion runners--the most dangerous job a Marine could have--remembered that the battalion went into action that day at T/O strength of slightly more than 1,000.

The Germans resisted furiously, desperate to prevent the collapse of their entire front. If Blanc Mont Ridge fell, the dominant feature of the entire region would be lost, and the Meuse River crossing would be wide open to the Americans. With Blanc Mont Ridge gone, the bastion of the Hindenburg Line would be irretrievably ruptured. The shell-ravaged white chalk slopes of the ridge became the scene of some of the most savage fighting of the war. For more than a week Marines fought with rifles, bayonets, hand grenades, knives and bare fists, prying tenacious German infantry from a maze of trenches and bunkers with names like the Essen Trench, the Kriemhilde Stellung and the Essen Hook.

When it was finally over, when all objectives had been secured, the 134 remaining members of 1st Bn, 5th Marines filed wearily down from the torn and blasted ridge. Among those they left behind was an unlikely 51-year-old platoon leader, a man whose courage and leadership were an inspiration to all who knew him. Yet, for all that, he was a man whose life had been spent erasing a dark secret of shame and disgrace. His story began years before.

He was born Henry Lewis Hulbert on January 12, 1867, in Kingston-Upon-Hull, Yorkshire, England. The first child of a prosperous merchant family, he was joined by a brother and three sisters. None of the children of Henry Ernest Hulbert and Frances (Gamble) Hulbert knew the want and deprivation that was the lot of so many children born into the industrial cities of the mid-19th century. Theirs was a childhood, if not of luxury, then certainly of abundance, an abundance that included a far better than average education.

For young Henry this meant matriculation at the prestigious and exclusive Felsted School in Essex, a school that traces its origins to 1564. At the age of 13, already showing signs of the tall, rangy, handsome young man he would become, Henry Lewis Hulbert found himself immersed in the demanding rigors of a classical education in mathematics, science, Latin, Greek and English literature. There was a purpose to all of this, for even at an early age the young Yorkshireman had determined upon a career in Britain's Colonial Civil Service. In 1884, not yet 18 years old, Henry Lewis Hulbert received his first appointment-clerk and storekeeper-in the Civil Service of the Malay State of Perak, today a part of the country of Malaysia.

The drive for excellence that was to mark the rest of his life manifested itself with superior performance that soon caught the eyes of his supervisors. Among those impressed was Robert Douglas Hewett, state auditor for Perak and right-hand man of the British Resident (governor) Frank Sweattenham. Soon young Hulbert was exercising authority and responsibility far beyond his years and exercising it exceedingly well. His records show such diverse assignments as Inspector of Public Works in Krian, District Engineer for Kuala Kangsar, Harbor Master for the port of Matang and District Magistrate for Kinta District.

He also acquired a sweetheart, Anne Rose Hewett, his mentor's sister, who had been born in Bombay, India. In June of 1888, with the approval and best wishes of the influential Hewett family, the two were married. A year later the young couple welcomed the arrival of a daughter, Sydney. It was, to all appearances, a perfect family.

Henry Lewis Hulbert's career was taking off. His own exceptional abilities and his marriage into a powerful family guaranteed his eventual rise to the top. Admired and respected by his peers and favored by his superiors, he was a man marked for success. Then, in the early summer of 1897, everything crashed down around him. Henry Lewis Hulbert had fallen deeply in love with his wife's younger sister, visiting from England. It had begun secretly two years earlier during a previous visit. Drawn irresistibly toward each other, they had become lovers. Then they were discovered, and the fury of the Hewett family descended like an executioner's axe.

The sister-in-law was immediately put aboard a ship bound for England, only to die tragically in a shipwreck during a storm on the homeward voyage. For Henry Lewis Hulbert there was banishment. He was sent packing with scarcely more than the clothes on his back, told to leave the Malay States and never return. A discreet and very quiet divorce followed.

Where does a man go when he flees disgrace and shame? For Henry Lewis Hulbert it was Skagway, jumping off point for Chilkoot Pass and the Klondike gold fields. The venture didn't pan out. By the following spring he had wandered to San Francisco. With war with Spain looming, Henry Lewis Hulbert enlisted in the Marine Corps on March 28, 1898, a 31-year-old private with a ruined life behind him and skimpy prospects before him. It is unlikely that he thought of it in such dramatic terms, but the moment he had spent his life waiting for had arrived. The exiled magistrate and the United States Marine Corps were made for each other.

Boot camp at Mare Island, Calif., was followed by assignment to the Marine Guard, USS Philadelphia (C-4) and the beginning of a remarkable record as a United States Marine. Barely more than a year after his enlistment, on April 1, 1899, during a combined British-American expedition in Samoa, Henry Lewis Hulbert was awarded the Medal of Honor for extraordinary heroism. When the landing force of British and American Marines and seamen was ambushed by a numerically superior rebel force, Private Hulbert, despite being wounded himself, conducted a one-man delaying action that enabled the landing force to withdraw to a defensible position covered by the guns of the warships offshore. Under fire from three sides, he stood his ground, refusing to withdraw until the main body had established a new defensive perimeter. Single-handedly he held off the attackers, while at the same time he protected two mortally wounded officers, Lieutenant Monaghan, USN and Lt Freeman, RN. In his official report of the action, Lt Constantine M. Perkins, commander of Philadelphia's Marine Guard, wrote of Pvt Hulbert: "His conduct throughout was worthy of all honor and praise."

When he left USS Philadelphia in 1902, Hulbert wore the chevrons of a sergeant. The years that followed saw his steady rise through the enlisted ranks. Serving in a succession of billets ashore and afloat that were representative of the era, he never missed an award of the Marine Corps Good Conduct Medal and never fired less than Expert Rifleman in his regular service rifle requalification. His conduct and proficiency marks were uniformly the highest that could be awarded, and his service records contain numerous commendations by reporting seniors. He was also gaining a reputation as a totally dependable noncommissioned officer, whose advice was sought by seniors and subordinates alike. A congenial and friendly man, whose knowledge and experience covered an array of subjects, and who delighted in good company and good conversation, he was described by a fellow Marine as having "the bearing and manners of a fine gentleman and the complete and all-embracing courtesy of an earlier generation." Yet even those who knew him best never heard him speak of his life before joining the Marine Corps.

By 1917 Hulbert had attained the grade of sergeant major, the Marine Corps' senior NCO of that grade, and he served on the personal staff of Major General Commandant George Barnett. He also had remarried, and he and his wife, Victoria, had settled into a modest house in Riverdale, Md., eventually to be joined by an infant daughter, Leila Lilian Hulbert. It was also in 1917, shortly before America's entry into World War I, that Hulbert appeared before an examining board to determine his fitness for appointment to the newly established grade of Marine gunner. On March 24, 1917, with the enthusiastic recommendation of the president of the examining board, Brigadier General John A. Lejeune, Henry Lewis Hulbert became the first Marine ever to wear the bursting bomb grade insignia of a Marine gunner.

Considered too old for combat at the age of 50, Gunner Hulbert nonetheless pressed to be among those sent to France. He could have remained safe and secure in his position in the office of the Major General Commandant, returning home each evening to his wife and daughter. Who would have expected a man of his years to go off to war? He did, and that was what was important. There was a war, and the old war horse could not sit idly by while other Marines fought it. Finally winning the approval of Gen Barnett, with whom he had a long and close association, Hulbert, again the Marine Corps' senior officer of his grade, sailed for France aboard the old transport Chaumont with the 5th Marines in July 1917.

In France they tried to give him a safe job out of the way at regimental headquarters, but they could not keep him there. At every opportunity--and he created plenty of opportunities--he found his way up to the front lines and indulged himself in a bit of free-lance fighting. Finally, the powers that be gave in to the inevitable. Gunner Hulbert, 51 years old, was assigned as a platoon leader with the 66th Company (later C Co), 1st Bn, 5th Marines. It did not take the enemy long to learn he was there.

Wounded in his regiment's first major engagement, at Belleau Wood on June 6, 1918, Gunner Hulbert was twice cited in official orders for acts of bravery. On one occasion, armed only with a rifle, he single-handedly attacked German machine-gun positions and, as the citation read, "left seven of the enemy dead and put the remainder to flight." The second citation commended him for continuing to lead his platoon in attacks that routed the defenders of a series of strong points despite being painfully wounded himself.

The platoon leader who was old enough to be the father of the men he led, whose stamina and endurance were the envy of men half his age, was not quite finished. A third act of heroism led him to be decorated with the distinguished Service Cross, one of the first Marines to be so recognized. In his official report of the monthlong fighting in Belleau Wood, Army MajGen Omar L. Bundy, commanding general of the 2d Division, United States Regular, in which the 5th Marines served as part of the famed Marine Brigade, singled out Hulbert, "for his extraordinary heroism in leading attacks against enemy positions on June 6th." MajGen Bundy concluded, "No one could have rendered more valuable service than Gunner Hulbert."

Gen Bundy was not alone in his praise. Captain George K. Shuler, USMC wrote, "I should be most glad to have Gunner Hulbert under me in any capacity, and should he through good fortune be promoted over me I should be most happy to serve under his command." Lt W. T. Galliford, himself a winner of the Distinguished Service Cross, remarked, "If the Fifth Regiment goes over the top, I want to go with Mister Hulbert." Gen John J. Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Force, personally recommended that Hulbert be directly commissioned as a captain.

Heroism under fire at Soissons, an action in which he was again wounded, saw Gunner Hulbert cited for bravery yet again, commissioned a second lieutenant and immediately promoted to first lieutenant. But the trail ahead of him was growing short. At Blanc Mont Ridge on Oct. 4, 1918, the Second Division's bloodiest single day of the war, it ended.

Approved by the Secretary of the Navy for promotion to the grade of captain, Henry Lewis Hulbert, up front as usual, was struck down by an unknown German machine-gunner. John W. Thomason saw him fall and noted the peaceful look upon his face. He was posthumously awarded the Navy Cross and cited for bravery a fourth time. The French government bestowed the Croix de Guerre Order of the Army upon this "most gallant soldier." Britannia's son, who gave his life for his adopted land, rests today in Virginia's Arlington National Cemetery. His name is among those inscribed on the Peace Cross at Bladensburg, Md., erected in 1919 to honor the memory of the men from Prince George's County who died in the Great War.

But the story of Henry Lewis Hulbert did not end with his death in France. On June 28, 1919, Victoria C. Hulbert, the widow of this inspirational Marine, christened the destroyer USS Henry L. Hulbert (DD-342) when it was launched at Norfolk, Va. Commissioned and put into service in 1920, Hulbert served continually on the Asiatic Station until 1929 when she returned to American waters, remaining there until she was decommissioned in 1934. Recalled to service in 1940, Hulbert was assigned to the Pacific Fleet and on Dec. 7, 1941, was moored at Berth D-3, Submarine Base, Pearl Harbor, territory of Hawaii. While Hulbert's whaleboats rescued seamen from stricken ships along Battleship Row, her .50-caliber antiaircraft battery brought down a Japanese torpedo bomber and damaged two others. The ship continued to serve in the Central and North Pacific until she was taken to Philadelphia and decommissioned for the last time in November 1945. In 1946, USS Henry L. Hulbert was stricken from the Navy List and sold for scrap.

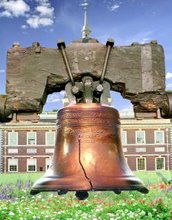

Saved from the scrap heap was the ship's bell. For more than 50 years that bell, along with others of its kind, mementos of long-gone ships of the line, collected dust in a warehouse at the Washington Navy Yard. Then, in July of 1998, thanks to the efforts of the Medal of Honor Society, the ship's bell of USS Henry L. Hulbert was rededicated at The Basic School's Infantry Officer Course at Quantico, Va. On the quarterdeck of Mitchell Hall, along with the decorations won by her ship's namesake, the bell stands as a reminder of the exemplary qualities of a magnificent Marine. What better inspiration for officers about to assume one of the Marine Corps' most demanding duties-infantry platoon leader-than a man whose dedication to duty and devotion to the Marine Corps continue to serve as an example years after his death on the battlefield?

Did Henry Lewis Hulbert find redemption? Did he regain his lost honor? You be the judge.

Author's note: Special thanks for assistance in the preparation of this article are due to Mary C. Leitch of Immingham, Lincolnshire, England. Without her detailed and exhaustive research efforts, nothing would be known of the early life of Henry Lewis Hulbert. From all Marines, a hearty "Well done!"

CITATION:

HULBERT, Henry Lewis

Private, U.S. Marine Corps

G.O. Navy Department, No. 55

July 19, 1901

For distinguished conduct in the presence of the enemy at Samoa, Philippine Islands, 1 April 1899.

He died on October 4, 1918 and was buried in Section 3 of Arlington National Cemetery.

Story by Major Allan C. Bevilacqua, USMC (Ret)

Archibald Henderson,

Archibald Henderson,