skip to main |

skip to sidebar

Bataan Islands and Corregidor

Bataan Islands and Corregidor

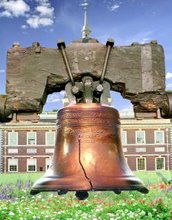

The American flags of the 4th Marine Regiment were burned to avoid capture on Corregidor on May 6, 1942. This is the last days of fighting before the order came to surrender to the Japanese. (Click on above map.)

Morning BattleDuring the morning action Major Williams fought beside his men, moving from position to position along the line. Captain Brook remembered, “He was everywhere along the line, organizing and directing our attack, always in the thick of it, seeming to bear a charmed life. I have heard men say that he was the bravest man they ever saw.”

From 0900 until 1030 the firefight proceeded without change in position. The lines were so close that none of the companies could shift a squad without drawing machine gun fire and artillery. All of the 4th Battalion was fighting without helmets, canteens, or even cartridge belts. However, the Marines had the advantage of being too close for the Japanese artillery to be of use. Small parties of Marines occasionally were dispatched to take out Japanese snipers who were firing into the rear of the Marine position from the beach area.

The Japanese were now facing a serious problem, which threatened to lose the battle for them. Each Japanese rifleman came ashore with 120 rounds of ammunition and two hand grenades. The machine gun sections carried only two cases totalling 720 rounds of ammunition and three to six grenades. The knee mortar sections had only 36 heavy grenades and three light grenades. A large quantity of additional ammunition had been loaded on the landing craft due to the expected problems in resupplying the force. However, the ammunition crates had been hurriedly dumped overboard by the crews of the landing craft as they grounded on Corregidor and now few boxes could be recovered in the murky water. By morning most of the Japanese on Denver Hill were either out of ammunition or very close to it. Many Japanese soldiers were now fighting with the bayonet and even threw rocks at the Marines to hold the hill.

At 0900, Captain Herman Hauck, USA, reinforced the Marines and sailors with 60 members of his Coast Artillery battery. Williams placed the soldiers on the beaches to his left where heavy losses had whittled away at his strength. With the reinforcements some advance was made, but against strong enemy resistance. Nevertheless, much of the fighting was done with the bayonet, as the Japanese were running out of ammunition. The tide was beginning to turn against the Japanese. As Lieutenant General Masaharu Homma reflected one year after the surrender, “If the enemy had stood their ground 12 hours longer, events might not have transpired as smoothly as they did.”

The Japanese were able to set up a mortar battery on North Point and opened with telling effect on Williams’ left companies. Two squads were sent out to flank the guns, but ran into machine gun fire which wiped out almost the entire right squad. Three more squads were sent out, two to the left and one to the right of the mortars. After heavy fighting and loss, the deadly mortars were silenced.

The machine gun at the head of the draw at Cavalry Point also had held up the progress of the advance. U.S. Army Lieutenant Otis E. Saalman of the 4th Battalion staff was ordered by Williams to go to the left and see what he could do to get the line moving. With the help of Captain Harold Dalness, USA, Saalman took a party of volunteers up the draw to silence the gun. The Americans crawled unobserved to within grenade range and then opened fire on the enemy with rifles and grenades. One of the Japanese defenders picked up a grenade and lifted it to throw it back at the Americans when it went off in his hand. The gun was at last silenced and the way lay open to link up with the 1st Battalion survivors to the east. Saalman was able to observe the Japanese landing area where he watched three Japanese tanks climbing off the beach.TanksThe Japanese landed three tanks, two Type 97 tanks and a captured M-3. Two other tanks were lost 50 yards offshore while landing with the 2d Battalion, 61st Infantry. The surviving tanks were stranded on the beach due to the steep cliffs and beach debris and were left behind by the advancing infantry. In one hour, the tank crews and engineers worked a path off the beach. When the tanks reached the cliffs, they found the inclines too steep and were unable to move further. The Marines were alerted to the presence of the tanks and Gunner Ferrell went to Cavalry Point to investigate the rumors of tanks, and found the vehicles apparently hopelessly stalled.

At daylight the Japanese were able to cut a road to Cavalry Beach but were still prevented from moving inland by the slope behind the beach. Finally, the captured M-3 negotiated the cliff and succeeded in towing the remaining tanks up the cliff. By 0830, all three tanks were on the coastal road and moved cautiously inland. At 0900, Gunnery Sergeant Mercurio reported to Malinta Tunnel the presence of enemy armor.

At 1000 Marines on the north beaches watched as the Japanese began an attack with their tanks, which moved in concert with light artillery support. Private First Class Silas K. Barnes fired on the tanks with his machine gun to no effect. He watched helplessly as they began to take out the American positions. He remembered the Japanese tanks’ guns “looked like mirrors flashing where they were going out and wiping out pockets of resistance where the Marines were.” The Marines still had nothing in operation heavier than automatic rifles to deal with the enemy tanks. Word of the enemy armor caused initial panic, but the remaining Marine, Navy, and Army officers soon halted the confusion.

One of the Marines’ main problems was the steady accumulation of wounded men who could not be evacuated. Only four corpsmen were available to help them. No one in the battalion had first aid packets, or even a tourniquet. The walking wounded tried to get to the rear, but Japanese artillery prevented any move to Malinta Tunnel. No one could be spared from the line to take the wounded to the rear. At 1030 the pressure from the Japanese lines was too great and men began to filter back from the firing line. Major Williams personally tried to halt the men but to little avail. The tanks moved along the North Road with Colonel Sato personally pointing out the Marine positions. The tanks fired on Marine positions knocking them out one by one. At last Williams ordered his men to withdraw to prepared positions just short of Malinta Hill.

With the withdrawal of the 4th and 1st Battalions, the Japanese sent up a green flare as a signal to the Bataan artillery which redoubled its fire, and all organization of the two battalions ceased. Men made their way to the rear in small groups and began to fill the concrete trenches at Malinta Hill. The Japanese guns swept the area from the hill to Battery Denver and then back again several times. In 30 minutes only 150 men were left to hold the line.

The Japanese had followed the retreat aggressively and were within 300 yards of the line with tanks moving around the American right flank. Lieutenant Colonel Beecher moved outside the tunnel, shepherding his men back to Malinta hill. He knew his men would be thirsty and hungry and ordered Sergeant Louis Duncan to “See what you can do about it.” Duncan broke open the large Army refrigerators near the entrance to Malinta Tunnel, and soon was issuing ice-cold cans of peaches and buttermilk to the exhausted Marines.

At 1130 Major Williams returned to the tunnel and reported directly to Colonel Howard that his men could hold no longer. He asked for reinforcements and antitank weapons. Colonel Howard replied that General Wainwright had decided to surrender at 1200. Wainwright agonized over his decision and later wrote, “It was the terror vested in a tank that was the deciding factor. I thought of the havoc that even one of these beasts could wreak if it nosed into the tunnel.” Williams was ordered to hold the Japanese until noon when a surrender party arrived.

At 1200 the white flag came out of the tunnel and Williams ordered his men to withdraw to the tunnel and turn in their weapons. The end had come for the 4th Marines. Colonel Curtis ordered Captain Robert B. Moore to burn the 4th Marines Regimental colors. Captain Moore took the colors in hand and left the headquarters. On return, with tears in his eyes, he reported that the burning had been carried out. Colonel Howard placed his face into his hands and wept, saying, “My God, and I had to be the first Marine officer ever to surrender a regiment.”

The news of the surrender was particularly difficult for the men of the 2d and 3d Battalions who were ready to repel any renewed Japanese landing. Private First Class Ernest J. Bales first learned of the surrender when a runner arrived at his gun position at James Ravine, who announced, “We’re throwing in the towel, destroy all guns.” Bales and his comrades found the news incredible, “hard to take . . . couldn’t believe it.” One Marine tried to shoot the messenger but was wrestled to the ground.Private First Class Ben L. Lohman of 2d Battalion destroyed his automatic rifle, but “we didn’t know what the hell was going on,” as Japanese artillery continued to pound Corregidor long after the surrender. “The word was passed,” recalled Lohman, “go into Malinta Tunnel.” The men packed up their few belongings and marched toward the Japanese. Three Marines of 3d Battalion refused to surrender and boarded a small boat and made their escape out into the bay.

Sergeant Milton A. Englin commanded a platoon in the final defensive line outside Malinta Tunnel, and was prepared to deal with the Japanese tanks with armor-piercing rounds from his two 37mm guns. As he waited for the Japanese, an Army runner came out of the tunnel, shouting, “You have to surrender, and leave your guns intact.” Englin yelled back, “No! No! Marines don’t surrender.” The runner disappeared, but returned 15 minutes later, saying, “You have to surrender, or you will be courtmartialled after all this is over when we get back to the States.” Englin obeyed the order, but destroyed his weapons, instructing his men, “We aren’t going to leave any guns behind for Americans to be shot with.” The 4th Marines, 1,487 survivors, many in tears, destroyed their weapons and burned the American flags, and waited for the Japanese to come.

The defenders of Hooker Point were cut off from the rest of the island and were the last to surrender. They had finished the Japanese survivors of the 2d Battalion, 61st Infantry, in the daylight hours and for the rest of the day faced little opposition. As evening approached, they heard the firing on Corregidor diminish, and Forts Hughes and Drum fell silent. First Lieutenant Ray C. Lawrence, USA, and his second in command Sergeant Wesley C. Little of Company D, formed his men together at 1700, and marched to Kindley Field under a bedsheet symbolizing a flag of truce. The Marines soon found Japanese soldiers, who took their surrender.

Marine casualties in the defense of the Philippines totaled 72 killed in action, 17 dead of wounds, and 167 wounded in action. Worse than the casualty levels caused by combat in the Philippines was the brutal treatment of Marines in Japanese hands. Of the 1,487 members of the 4th Marines captured on Corregidor, 474 died in captivity.

The Japanese recognized that the five-month battle for the Philippines was seen by the world as a defining contest of wills between the United States and Japan. Lieutenant General Masaham Homma, Japanese commander in the Philippines, recognized the critical nature of this conflict when he addressed his combat leaders in April 1942, saying:

The operations in the Bataan Islands and the Corregidor Fortress are not merely a local operation of the Great East Asia War . . . the rest of the world has concentrated upon the progress of the battle tactics on this small peninsula. Hence, the victories of these operations also will have a bearing upon the English and the Americans and their attitude toward continuing the war. And so they did.

Japanese Victory Parade Through Manila, Capital of the Philippine Islands

Sources

The capture and subsequent loss in 1942 of the original 4th Marines’ records prove at first daunting to any researcher of the period. The search for source material must begin with part IV of LtCol Frank 0. Hough, Maj Verle E. Ludwig, and Henry I. Shaw, Jr.’s History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II, vol 1, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal (Washington: HistBr, G-3 Div, HQMC, 1958). This work proved to be the single best account of the regiment in the fall of the Philippines.

Other works of value include Hanson W. Baldwin’s “The Fourth Marines on Corregidor,” Marine Corps Gazette, Nov46-Feb47; Louis Morton, The Fall of the Philippines, The War in the Pacific: United States Army in World War II (Washington: Office of the Chief of Military History, 1953). Also useful were James H. and William M. Belote, Corregidor: The Saga of a Fortress (NY: Harper and Row, 1967); Reports of General MacArthur, vols I and II (Washington: GPO, 1966); Carl M. Holloway, Happy, the POW, (Brandon, Mississippi: Quail Ridge Press, 1981); Donald Versaw, The Last China Band (Lakewood, California: Peppertree Publications, 1990); and William R. Evans, Soochow and the 4th Marines (Rogue River, Oregon: Atwood Publications, 1987).The 4th Marines records which were brought out from Corregidor by submarine or retrieved from the prison camps after the war are found in the geographical and subject files in the Archives Section, Marine Corps Historical Center. The Personal Papers Collection proved to contain valuable items, including the Thomas R. Hicks journals, which contain a daily record of events of the regiment. Also of use were the Reginald H. Ridgely papers, Curtis T. Beecher memoir, Floyd 0. Schilling papers, Cecil J. Peart papers, James B. Shimel papers, Carter B. Simpson memoir, Wilbur Marrs memoir, and the Charles R. Jackson manuscript.Many other articles written by Marine participants or about the 4th Marines in the defense of the Philippines were consulted for this work.

The best sources, by far, for the 4th Marines experience in the fall of the Philippines are the survivors themselves. Capt Elmer E. Long, Jr., USMC (Ret) and CWO Gerald A. Turner, USMC (Ret), provided assistance in locating the surviving members of the “Old” 4th. More than 100 Marines have been interviewed as well as men from other services

My Adopted Hometown Gulf Breeze, Florida

My Adopted Hometown Gulf Breeze, Florida

Gulf Breeze is a city located on the Fairpoint Peninsula in Santa Rosa County, Florida and is a suburb of Pensacola, FL. The population was 5,665 at the 2000 census. As of 2004, the population recorded by the U.S. Census Bureau is 6,333, an 11.79 percent increase.

History

Gulf Breeze shares the rich history of Pensacola Bay. Shell mounds here date back over one thousand years, evidence of the Native Americans desire for seafood. The first European settlement was attempted in 1559 by Tristan de Luna, but was abandoned two years later. The Spanish returned in 1698, but transferred all of Florida to the British in 1763. It was the British who named Town Point. English Navy Cove was the area where ships were careened, a process of hauling ships aground to allow the hulls to be scraped free of barnacles.

Florida became American territory in 1821, and by 1824 a road ran through the peninsula all the way to St. Augustine. Part of this road can be traced in the Naval Live Oaks Reservation of the Gulf Islands National Seashore today. President John Quincy Adams authorized Naval Live Oaks, a federal tree farm dedicated to providing live oak timber for U.S. Navy ships, in 1828.

The Pensacola Navy Yard across the bay from Fair Point dates to 1825, and the Army began building forts to protect the yard and Pensacola Bay in 1829. Beginning with Fort Pickens, the Army built harbor forts off and on through World War II, all of which are located within the Gulf Islands National Seashore (a unit of the National Park System). Fort Pickens was one of only four forts in the South to be held by the Union for the duration of the American Civil War. In November 1861, Union-held Fort Pickens exchanged 6000 rounds of cannon fire for two days with Confederates at Fort Barrancas and Fort McRee. Both Confederate held forts were heavily damaged and the Confederates abandoned the area in May 1862.

In 1931 the first bridge across Pensacola Bay was opened to Gulf Breeze with great fanfare. This concrete drawbridge connected the cities until they were replaced by the current bridge 1960. The original bridge was converted into two fishing piers. Hurricane Ivan in 2004 substantially destroyed the fishing piers, and demolition of the remaining portion of the structure is ongoing as of 2007.

A wooden bridge to Pensacola Beach was also built in 1931; this structure was replaced with a concrete drawbridge in 1951. It, too, was repurposed as a fishing pier following the construction of a taller span, the Bob Sikes Bridge, in 1973.

Gulf Breeze traces its name to the Gulf Breeze Cottages and Store, which opened a post office branch in 1936 where Beach Road Plaza now stands. The community began to grow following the opening of the improved bay bridge in 1960, and continues to grow today.

From 1995 to 2005, Gulf Breeze has received several direct hits and severe blows from numerous hurricanes. In 1995, Hurricane Erin and Opal made landfall just south of the city. While Erin caused moderate damage to the area, Hurricane Opal devastated much of the community. Nine years later, in 2004, Hurricane Ivan made landfall west of the Gulf Breeze but caused widespread damage in the city, destroying many homes and businesses. In 2005, Hurricane Dennis passed just east of the city. Damage from this storm was more severe than that received in communities lying further west.

The City of Gulf Breeze is now often referred to as "Gulf Breeze Proper." This differentiates it from other communities further east which are assigned Gulf Breeze addresses by the U.S. Postal Service but lie outside of the city limits.

Growth of the city itself is geographically restricted, surrounded by major water bodies on three sides. Additionally, the eastern portion of Gulf Breeze is occupied by the Naval Live Oaks Reservation. As a result, new growth occurs outside of the city limits along U.S. Highway 98. This growth has been tremendous; many new subdivisions, schools, fire and police stations, and businesses have been built within a few miles of Gulf Breeze Proper.

Point of Interest

Gulf Breeze became famous in 1987 as the site of several UFO sightings. It has been referred to as the UFO capital of the United States.

AAA has designated Gulf Breeze as also one of seven "strict enforcement areas" for traffic laws in the United States. This rating is one level short of speed trap, and is only shared by six other cities and towns nationwide.

Gulf Breeze also received media attention for instituting a program to allow volunteers to drive police cars within the city and report traffic violations to police. Volunteers receive training in radio use and first aid but are not empowered to make arrests or traffic stops. The City of Gulf Breeze is known as a "Speed trap" due to a major east-west highway (U.S. HWY. 98) dividing the City in half.

Demographics

As of the census of 2000, there were 5,665 people, 2,377 households, and 1,678 families residing in the city. The population density was 460.5/km² (1,192.0/mi²). There were 2,553 housing units at an average density of 207.5/km² (537.2/mi²). The racial makeup of the city was 97.39% White, 0.25% African American, 0.55% Native American, 0.56% Asian, 0.02% Pacific Islander, 0.18% from other races, and 1.06% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.36 percent of the population.

There were 2,377 households out of which 28.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 57.7% were married couples living together, 10.6% had a female householder with no husband present, and 29.4% were non-families. 25.3% of all households were made up of individuals and 13.0% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.36 and the average family size was 2.83.

In the city the population was spread out with 22.3 percent under the age of 18, 4.6 percent from 18 to 24, 22.5% from 25 to 44, 29.7% from 45 to 64, and 20.8% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 45 years. For every 100 females there were 89.4 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 83.6 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $52,522, and the median income for a family was $61,661. Males had a median income of $44,408 versus $28,159 for females. The per capita income for the city was $34,688. About 3.8% of families and 4.2 percent of the population were below the poverty line, including 5.5 percent of those under age 18 and 1. percent of those age 65 or over.

Alan Shepard - First US Astronaut

Alan Shepard - First US Astronaut

Alan Bartlett Shepard, Jr. (November 18, 1923 – July 21, 1998) (Rear Admiral, USN, Ret.) was the second person and the first American astronaut in space.

Education

Born in East Derry, New Hampshire, Shepard graduated from Admiral Farragut Academy in 1941, received a Bachelor of Science degree from the United States Naval Academy at Annapolis in 1944, an Honorary Master of Arts degree from Dartmouth College in 1962, an Honorary Doctorate of Science from Miami University (Oxford, Ohio) in 1971, and an Honorary Doctorate of Humanities from Franklin Pierce College in 1972. He graduated from the United States Naval Test Pilot School in 1951 and the Naval War College, Newport, Rhode Island in 1957.

Naval career

Shepard began his naval career after graduation from Annapolis, on the destroyer USS Cogswell deployed in the Pacific Ocean during World War II. He subsequently entered flight training at Corpus Christi, Texas and Pensacola, Florida, and received his wings in 1947. His next assignment was with Fighter Squadron 42 at Norfolk, Virginia and Jacksonville, Florida. He served several tours aboard aircraft carriers in the Mediterranean while with this squadron.

In 1950, he attended the U.S. Naval Test Pilot School at Patuxent River, Maryland. After graduation, he participated in flight test work which included high-altitude tests to obtain data on light at different altitudes and on a variety of air masses over the American continent; test and development experiments of the Navy's in-flight refueling system; carrier suitability trials of the F2H-3 Banshee; and Navy trials of the first angled carrier deck. He was subsequently assigned to Fighter Squadron 193 at Moffett Field, California, a night fighter unit flying Banshee jets. As operations officer of this squadron, he made two tours to the western Pacific on board the carrier USS Oriskany.

He returned to Patuxent for a second tour of duty and engaged in flight testing the F3H Demon, F8U Crusader, F4D Skyray, and F11F Tiger. He was also project test pilot on the F5D Skylancer, and his last five months at Patuxent were spent as an instructor in the Test Pilot School. He later attended the Naval War College at Newport, Rhode Island, and upon graduating in 1957 was subsequently assigned to the staff of the Commander-in-Chief, Atlantic Fleet, as aircraft readiness officer.

He logged more than 8,000 hours flying time—3,700 hours in jet aircraft.

Shepard aboard Freedom 7

Astronaut career

Shepard was one of the Mercury astronauts named by NASA in April 1959 to Project Mercury, and he holds the distinction of being the first American to journey into space, as well as the only Mercury astronaut to walk on the Moon. On May 5, 1961, in the Freedom 7 spacecraft, he was launched by a Redstone rocket on a ballistic trajectory suborbital flight—a flight which carried him to an altitude of 116 statute miles and to a landing point 302 statute miles down the Atlantic Missile Range. Shortly before the launch, Shepard stated "Please, dear God, don't let me fuck up." This has since become known among aviators as "Shepard's Prayer."

Shepard did not fuck up - God did indeed keep him safe. On May 5, 1961, US Marine pilots retrieved astronaut US Navy Cdr. Alan Shepard from the water landing zone.

According to Gene Kranz in his book Failure Is Not an Option: "When reporters asked Shepard what he thought about as he sat atop the Redstone rocket, waiting for liftoff, he had replied, 'The fact that every part of this ship was built by the low bidder.'"

Later, he was scheduled to pilot the Mercury-Atlas 10 Freedom 7-II, three day extended duration mission in October 1963. The MA-10 mission was cancelled on June 13, 1963. He was the back-up pilot for Gordon "Gordo" Cooper for the MA-9 mission.

After the Mercury-Atlas 10 mission was cancelled in June 1963, Shepard was designated as the command pilot of the first manned Gemini mission. Thomas Stafford was picked as his co-pilot. But in early 1964, Shepard was diagnosed with Ménière's disease, a condition in which fluid pressure builds up in the inner ear. This syndrome causes the semicircular canals and motion detectors to become extremely sensitive, resulting in disorientation, dizziness, and nausea. This condition caused him to be removed from flight status for most of the 1960s (Gus Grissom and John Young were assigned to Gemini 3 instead).

Also in 1963, he was designated Chief of the Astronaut Office with responsibility for monitoring the coordination, scheduling, and control of all activities involving NASA astronauts. This included monitoring the development and implementation of effective training programs to assure the flight readiness of available pilot/non-pilot personnel for assignment to crew positions on manned space flights; furnishing pilot evaluations applicable to the design, construction, and operations of spacecraft systems and related equipment; and providing qualitative scientific and engineering observations to facilitate overall mission planning, formulation of feasible operational procedures, and selection and conduct of specific experiments for each flight.

He was restored to full flight status in May 1969, following corrective surgery (using a newly developed method) for Ménière's disease. He was originally assigned to command Apollo 13, but as it was felt he needed more time to train, he and his crewmates (lunar module pilot Edgar Mitchell and command module pilot Stuart Roosa) swapped missions with the then crew of Apollo 14 (James Lovell, Ken Mattingly - who was himself replaced by Jack Swigert shortly before the mission - and Fred Haise).

At age 47, and the oldest astronaut in the program, Shepard made his second space flight as commander of Apollo 14, January 31–February 9, 1971, man's third successful lunar landing mission. Shepard was a Rear Admiral when he retired from the Navy and the Astronaut Corps on August 1, 1974.

Awards and honors

During his life he was awarded the Congressional Space Medal of Honor; two NASA Distinguished Service Medals, the NASA Exceptional Achievement Medal, Naval Astronaut Wings, the Navy Distinguished Service Medal, and the Distinguished Flying Cross; recipient of the Langley Award (highest award of the Smithsonian Institution) on May 5, 1964, the Lambert Trophy, the Iven C. Kincheloe Award, the Cabot Award, the Collier Trophy, the City of New York Gold Medal (1971), Achievement Award for 1971.

Shepard was appointed by the President in July 1971 as a delegate to the 26th United Nations General Assembly and served through the entire assembly which lasted from September to December 1971.

Shepard is also remembered for being the only person to play golf on the Moon with a Wilson six-iron head attached to a lunar sample scoop handle. His first shot, which he duffed, only went a hundred feet, but his second shot, which he hit squarely (with only one arm, as the bulkiness of his 21-layer spacesuit prevented him from using both arms), sent the ball as he said "miles and miles."

The Navy named a supply ship, Alan Shepard (T-AKE-2), for him in 2006. A geodesic dome was built in his honor in Virginia Beach, Virginia but demolished in 1994. Interstate 93 in New Hampshire, from the Massachusetts border to its intersection with Route 101 in Manchester, is named in his honor. It passes through his native Derry.

Derry almost changed its name to "Spacetown", considering it in honor of his career as an astronaut.

His high school alma mater in Derry, Pinkerton Academy, has a building named after him, and the school team name is the Astros after his career as an astronaut.

Alan B. Shepard High School, in Palos Heights, Illinois, which opened in 1976, was named in his honor. Framed newspapers throughout the school depict various accomplishments and milestones in Shepard's life. Additionally, an autographed plaque commemorates the dedication of the building.

Later years

Always a shrewd businessman, Shepard was the only astronaut to become a millionaire while still in the program. After he left the program, he served on the boards of many corporations under the auspices of his Seven-Fourteen Enterprises (named for his two flights, Freedom 7 and Apollo 14).

In 1988, he teamed up with fellow Mercury Seven astronaut Deke Slayton to write Moon Shot: The Inside Story of America's Race to the Moon It was turned into a TV miniseries in 1994.

Shepard died of leukemia near his home in Pebble Beach, California on July 21, 1998, at age 74, two years after being diagnosed with that disease. His wife of 53 years, the former Louise Brewer, died five weeks afterward. They had two daughters, Laura (born in 1947) and Juliana (born in 1951), and had also raised a niece, Alice (born in 1951). He also had six grandchildren. Laura had a daughter, Lark and son, Bart. Juliana had a daughter, Ethney and son, Shepard. Alice had a son, Reid, and a daughter, Heather.

Like other astronauts, Shepard has many schools and other institutions named in his honor, including the Alan B. Shepard Post Office in his birthplace of Derry, New Hampshire.

Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University

Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University

(The picture is Burruss Hall, signature building on the Virginia Tech campus.)

Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, better known as Virginia Tech, is a public land grant polytechnic university in Blacksburg, Virginia, USA. Although it is a comprehensive university with many departments, the agriculture, engineering, architecture, forestry, and veterinary medicine programs are considered to be among its strongest. It is also one of the few public universities in the United States, along with Texas A&M University, which continues to maintain a corps of cadets (a full-time military training component within a larger civilian university).

In addition to its research and academic programs, Virginia Tech is known for its campus and location in the New River Valley of southwestern Virginia in the Blue Ridge Mountains, a part of the Appalachian Mountains. The university's public profile has also been raised significantly in recent years by the success of its football program.

History

In 1872, the Virginia General Assembly purchased the facilities of a small Methodist school called the Olin and Preston Institute in rural Montgomery County with federal funds provided by the Morrill Act. The Commonwealth incorporated a new institution on that site, a state-supported land grant military institute called the Virginia Agricultural and Mechanical College.

Under the 1891-1907 presidency of John M. McBryde, the school reorganized its academic programs into a traditional four-year college setup (including the renaming of the mechanics department to engineering); this led to an 1896 name change to Virginia Agricultural and Mechanical College and Polytechnic Institute. The "Agricultural and Mechanical College" section of the name was popularly omitted almost immediately, though the name was not officially changed to Virginia Polytechnic Institute until 1944 as part of a short-lived merger with what is now Radford University. VPI achieved full accreditation in 1923, and the requirement of participation in the Corps of Cadets was dropped from four years to two that same year (for men only; women, when they began enrolling in the 1920s, were never required to join).

VPI President T. Marshall Hahn, whose tenure ran from 1962 to 1974, was responsible for many of the changes that shaped the modern institution of Virginia Tech. The merger with Radford was dissolved in 1964, and in 1966, the school dropped the two-year military Corps training requirement for its male students. In 1973, women were allowed to join the Corps; Virginia Tech was the first school in the nation to open its military wing to women. One of Hahn's more controversial missions was only partially achieved. He had visions of renaming the school from VPI to Virginia State University, reflecting the status it had achieved as a full-fledged public education & research university. As part of this move, Virginia Tech would have taken over control of the state's other land-grant institution, a historically black college in Ettrick, Virginia, south of Richmond, then called Virginia State College. This plan failed to take root, and that school eventually became Virginia State University. As a compromise, VPI added "and State University" to its name in 1970, yielding the current formal name of Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. In the early 1990s, the school quietly authorized the official use of Virginia Tech as equivalent to the full VPI&SU name. Many school documents today use the shorter name, though diplomas and transcripts still spell out the formal name. Similarly, the abbreviation VT is far more common today than VPI or VPI&SU, and appears everywhere, from athletic uniforms, to the university's Internet domain name vt.edu.

Massacre

Virginia Tech was the site, April 16, 2007, of a school shooting that claimed 33 lives. Preliminary investigation pointed to Cho Seung-hui, a 23-year-old South Korean undergraduate student at the university, who was suspected to have acted alone.

Admissions

For the fall 2006 freshman class, Virginia Tech received 19,046 applications and accepted 67% of applicants (about 12,700). 39% of those accepted (approximately 5000 students) chose to enroll. Approximately 21 percent of the freshman class was filled by early decision candidates. Average grades increased, but SAT scores declined slightly. The typical fall 2006 freshman had a high school grade point average of 3.74, with a middle range of 3.38 to 3.95. The average cumulative SAT score was 1201, down two points from the previous year's average of 1203.

Academies

Virginia Tech offers 60 Bachelor's degree programs and 140 Master's and Doctoral degree programs through the College of Agriculture & Life Sciences, the College of Architecture & Urban Studies, the College of Liberal Arts and Human Sciences, the Pamplin College of Business, the College of Engineering, the College of Natural Resources, the College of Science, and the Virginia-Maryland Regional College of Veterinary Medicine. The College of Agriculture and Life Sciences offers the only two-year associate's degree program on campus, in agricultural technology. The ten most popular majors for the incoming class of 2005 were University Studies (Undeclared), General Engineering, Business (Undeclared), Biology, Communication, Psychology, Marketing, Political Science, Animal and Poultry Sciences, and Architecture.

Virginia Tech ranked 34th among national public universities and 77th among all national universities. Its College of Engineering undergraduate program was ranked 9th among engineering schools at public universities and 17th in the nation among all accredited engineering schools that offer doctorates. Seven different undergraduate programs in the College of Engineering are ranked in the top 25 among peer programs nationally - the industrial engineering program is ranked 7th; civil engineering, 11th; environmental engineering, 11th; mechanical engineering, 15th; aerospace engineering, 16th; electrical engineering, 20th; and chemical engineering, 23rd. Its Pamplin College of Business undergraduate program is ranked 22nd among the nation's public institutions and 52nd among all undergraduate business programs.

The architecture and landscape architecture programs in Virginia Tech's College of Architecture and Urban Studies are ranked among the very best in America. In its 2006 report, DesignIntelligence, the only national college ranking survey focused exclusively on design, ranked the undergraduate architecture program 7th nationally and 4th in the East. DesignIntelligence also ranked the university’s undergraduate landscape architecture program 8th in the nation and 2nd in the East.

The university's academic community has coined a word associated with the distribution of old test and study materials, referred to as "koofers".

On January 3, 2007 Virginia Tech along with Carilion Health System announced the creation of a new medical school that will be a joint venture between the two organizations. The first class is scheduled to be admitted in either 2009 or 2010. The new medical school will have approximately 40 students per class, making it a very small medical school. It will be located in Roanoke next to the Carilion Health System hospital.

Campus The Virginia Tech campus is located in Blacksburg, Virginia. The central campus is roughly bordered by Prices Fork Road to the northwest, Plantation Drive to the west, Main Street to the east, and 460-bypass to the south, though it has several thousand acres beyond the central campus. The university has established branch campus centers in Hampton Roads (Virginia Beach), the National Capital Region (Falls Church - Alexandria, Virginia), Richmond, Roanoke, and the Southwest Virginia Higher Education Center in Abingdon.

On the Blacksburg campus, the majority of the buildings incorporate Hokie Stone as building material. Hokie Stone is a medley of different colored limestone, often including dolomite. Each block of Hokie Stone is some combination of gray, brown, black, pink, orange, and maroon. The limestone is mined from various quarries in Southwestern Virginia, Tennessee, and Alabama, one of which has been operated by the university since the 1950s. An example of architecture incorporating Hokie Stone is Torgersen Bridge, a relatively new building on Virginia Tech's campus.

Virginia Tech also has one of the top dining programs in the country; it is currently ranked #2 by the Princeton Review. It has seven dining centers which included Squires food court (Au Bon Pain & Sbarro), Owens Food Court, Hokie Grill (Chick-fil-A, Pizza Hut, Cinnabon), D2 & DXpress, Shultz & Shultz Express, Deets Place, and the high end West End Market. Virginia Tech also has a catering center, Personal Touch Catering.

The University is protected by its own Police force, the Virginia Tech Police.